K N Ganesh

THE recommendation of the three member committee constituted by the Indian Council of Historical Research to review the fifth volume of the Dictionary of Martyrs: Indian Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) to strike down 387 entries from the dictionary has sparked off a controversy. The names to be struck down have included those executed by the British administration to suppress the Malabar rebellion of 1921. The act by the ICHR has acquired additional political dimension, as the RSS has been conducting a vitriolic hate campaign against the rebels of 1921, calling them ‘jihadist’ perpetrating Islamic fundamentalist agitation against the Hindus in order to setup an Islamic State in India. An entire issue of the RSS organ The Organiser was devoted for using the centenary of the Malabar rebellion as a pretext for their Anti-Islamic propaganda.

It is possible that those outside Kerala state may miss the significance of the ICHR action as actual course of Malabar rebellion may be unfamiliar to them. Even the standard history textbooks contain only a brief entry regarding the revolt of the ‘Moplahs’ and often attribute to it a religious sectarian character. Hence providing a brief resume of the events of the rebellion appears necessary before we go into the political import of the ICHR action.

THE SETTING OF

THE REBELLION

The district of Malabar carved out of the many medieval states that existed in North Kerala was formed in 1792. The city of Kozhikode became its headquarters, and the northern part of Malabar was administered from Thalassery and the southern part from Cherpulassery. Later, a revenue office was set up in Tirurangadi. The southern part of Malabar consisted of Eranad, Valluvanad and Ponnani taluks. Majority of the events of Malabar rebellion took place in the taluk of Eranad, with some spillovers to Ponnani and Valluvanad also.

Before British occupation, vast parts of Eranad was controlled by the princely house of Zamorins, who remained the major landlords under the British also. There were also other landlords including the house of Nilambur and a few other brahmana households. A number of Nayar houses, who were earlier the militia and revenue collectors of the Zamorins also came to acquire the landlord or jenmi status under the British. The original cultivators of the area were the servile dalit and backward castes along with Nayars who served as militia for the Zamorins and other princely houses. From sixteenth century, there was a gradual migration of the Muslims into the area from the coastal region. The Muslims originally appeared as traders and small farmers, but as their migrations increased , they were also absorbed into the existing landlord tenant relations, as tenant cultivators.

Muslim migration to the interior was thrust upon them by the activity of European traders in the Arabian Sea. The Muslims who were the most active traders, sailors and middlemen in the Arabian sea (the term ‘Mappila’ indicates their middleman status) were driven out of their position by the European traders, culminating in the near total control of the Malabar coast (with the exception of the French port of Mahe) by the English East India Company. The Muslim traders were reduced to the status of the middlemen for the company and their dependents were forced to migrate to the interior. This resulted in the growth of anti-British, and anti-European sentiments against them. Mappilas of Malabar fought alongside the army of Tipu Sultan in the battles fought against the British in Malabar. After the British occupation they were active supporters of the Pazhassi rebellion against the British (1802-1806).

The revenue settlement of the British privileged the erstwhile landlords, including princely houses, brahmanas and their lackeys as the revenue paying farmers while not disturbing the earlier landlord tenant relations. This allowed the landlords to transfer their revenue burden on to their tenant who were reduced to the position of tenants at will. Their rents were increased arbitrarily and they were also subjected to arbitrary evictions. The traders working in interior markets were subjected to heavy tolls. All these deteriorated the conditions of the tenants, local traders and middlemen. This increased the antagonism of the tenant cultivators, small farmers and traders against the British and the privileged classes of landlords, that were to erupt in numerous revolts across nineteenth century, referred to as ‘Mappila revolts’.

An examination of the revolts shows that they were localised and episodic in character, based on local issues and conflicts. The conflicts were between local landlords and their lackeys on the one side and the tenant cultivators, small farmers and local peddlers on the other. Vast majority of the rebels were Mappilas and there is some evidence of participation of other groups also. There was little connection between one revolt and the other. The British administrators attributed the revolts to the machinations of a group of spiritual leaders or the Sayyids and ended up deporting most influential of the Sayyids, Sayyid Fasl of Mamburam from Malabar during 1852. This only increased the antagonism of Mappila Muslims against the British resulting in the murder of the collector of Malabar, Thomas Connolly. A repressive regime was clamped down in the entire south Malabar, with a specific police force, Malabar Special Police being constituted only for the purpose.

The living conditions in South Malabar further deteriorated during the early years of twentieth century. With the onset of the ‘war economy’ during the First World War, prices soared, famine conditions prevailed. People remember a period when they were forced to subsist on ‘roots and grass’, and no help was coming from any quarter. The support to national movement also increased particularly among the tenant cultivators and they sought to raise the tenant question as primary issue facing the people in the national Congress meetings, like the conference at Manjeri in 1919.The participation of Turkey in the first world war aroused the hopes of the Muslim intelligentsia, who thought that the defeat of the Britain and their allies will further a process that would secure freedom for them. Their hopes were dashed when the allied forces won the war, and imposed the Treaty of Sevres on Turkey during 1920 dismantling the Ottoman Empire and the role of the Khalifah.

THE REBELLION

The historical setting of the Malabar rebellion shows that there were sufficient conditions for the growth of antagonism between the Malabar peasantry of south Malabar, a large section of them being Mappila Muslims and the British along with the antagonisms between landlords and tenants in which the religious identities of the conflicting sections played a relatively minor role; desecration of shrines takes place only in one incident during 18th century, and religious conversion becomes an issue in an incident during 19th century. All other conflicts have been directly related to colonial or landlord oppression. The anti-British sentiment among the Mappila Muslims was also visible from the beginning. The khilafat, normally considered as contributing to the ‘religious fervour’ of the Mappilas come into their midst only after the Lucknow pact of Indian National Congress and Muslim League in 1916, and gathered momentum in the region only after the world war, as a stimulus for the fight for freedom among the people, to which a section of the Muslim intelligentsia also extended their support. The case of Ali Musaliar, who was educated at Cairo and served in Kavaratti in Lakshadweep before taking charge as the Khatib of Tirurangadi Mosque is a case in point. Ali Musaliar was a staunch Gandhian and supporter of Congress and Khilafat when the rebellion broke out.

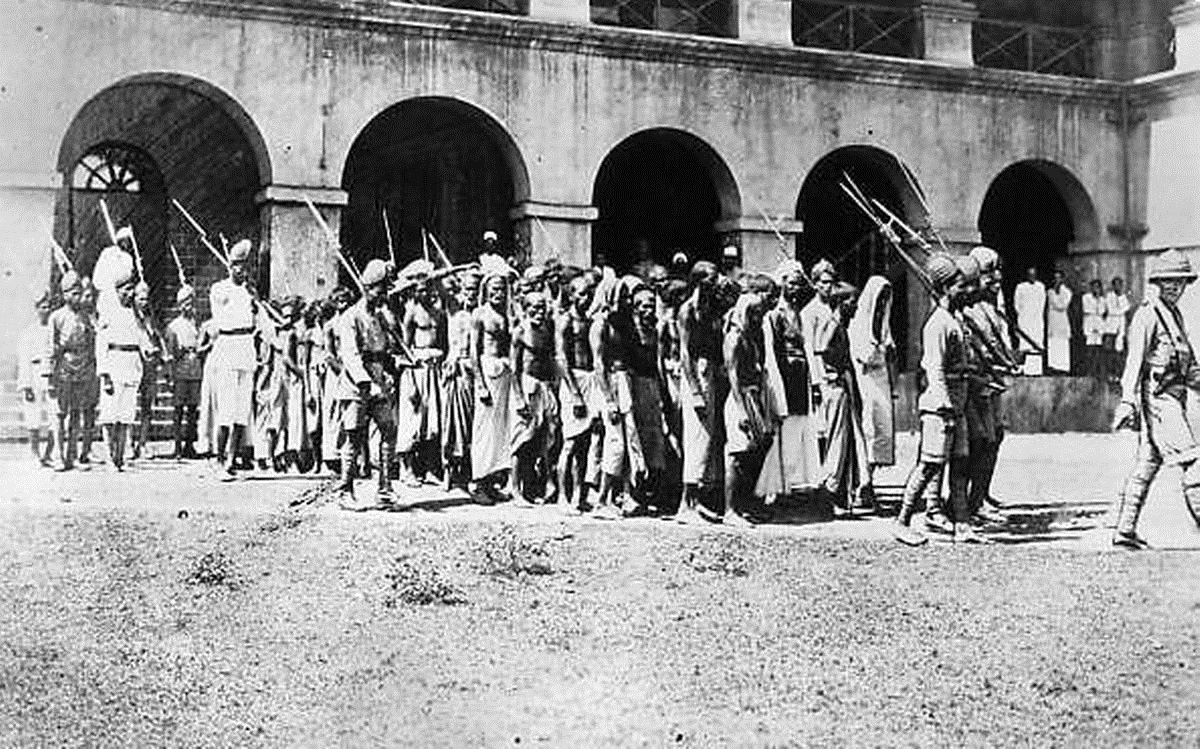

It is not necessary to provide blow by blow account of the rebellion. The rebellion started in August, when a Khilafat activist was arrested on false charges of pilfering a sword kept by Nilambur Raja, one of the landlords. The revolt soon spread to nearby Tirurangadi when rumours spread that the police had raided the mosque in their effort to arrest Ali Musaliar. The police had to face a massive gathering from all the nearby villages, which did not disperse even after police firing. The news of the ‘battles’ at Pookkottur and Tirurangadi spread all over south Malabar and soon revolts broke out at Malappuram, Perinthalmanna, Pandikkad and other regions. Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji, Chembrassery Thangal, Seethikkoya thangal, Kunjikader became the leaders of the revolt at various points. Roads were blocked, telephone lines cut, and the accounts office at Tirurangadi was set on fire. The British administration clamped down martial law, declared the Eranad taluk out of bounds for all outsiders, including Congress and Khilafat activists. The rebels responded by declaring separate areas as khilafats, each khilafat being put under the charge of one khilafat leader. Military troops were brought from different parts and after prolonged fighting, the rebellion was put down. All the Khilafat leaders including Ali Musaliar and Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji were executed. A number of the rebels were deported to Andaman Islands. The number of people killed in various police actions has not been estimated, and all the local memories testify that the British official reports underplayed the impact of the police and military action in the region. In a gruesome incident, about 90 people from the village of Karimpanal were shoved into a rail wagon and were taken from Tirur to Podanur near Coimbatore. On opening the wagon it was found almost all had died due to asphyxiation. The remaining died soon after. The rebellion had petered out by November 2021.

THE DEBATE ON

THE REBELLION

In a period when information from the rebellious regions was completely blocked out, outsiders had to depend on the official sources and stray news coming from people fleeing from the region. The British administration officials such as E F Thomas and Tottenham insisted on giving the rebellion a communal colour and presented the rebellion as a Muslim religious revolt against the British as well as the Hindus. Incidents of violence and plunder of landlord households particularly during the end of the rebellion were presented as evidence for their reasoning. A section of the Congress men led by K Madhavan Nair, a native of Manjeri, one of the centers of the revolt regarded the rebellion as nationalist, but they were in a minority within the Congress as most of them appeared to regard the rebellion as against the Hindus. Soumyendranath Tagore, a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party during 1934, was one of the first to regard the rebellion as a peasant revolt.

During 1946, on the 25th anniversary of the rebellion, the Communist Party brought out a document, drafted by E M S Namboodripad, named ‘The Call and the Warning”. The document analysed the historical circumstances in which the rebellion took place, in which the Mappila peasantry of Eranad were oppressed both by landlords and the British colonialism, and had no other option other than to revolt against the oppressors. The impetus provided by the Khilafat and the national movement provided them with the necessary resources to organise the revolt. However, with the arrest and later execution of the Khilafat leaders, the movement began to scatter, owing to the lack of leaders with necessary vision and resources. Anarchist communal elements that infiltrated the rebels succeeded in driving the rebellion against the Hindus. Thus a major rebellion against the landlords and British state degenerated into communal violence. The document presented the rebellion as a case study in the conduct of peasant struggles and the necessity of a politically cohesive organisation and leadership that would be able to break free from any form of containment and repression, as well as from divisive practices.

THE DEBATE ON

REBELLION TODAY

Subsequent research on Malabar rebellion by scholars such as Conrad Wood, Robert L Hardgrave, and K N Panikkar has vindicated the position taken by the Communist Party on Malabar rebellion. However, some scholars such as Stephen Dale have emphasized Mappila Muslim consciousness that has played a role in fomenting the rebellion. Some scholars sympathetic to an Islamist position, have also talked of a ‘Muslim psyche’ that formed the political consciousness giving rise to the rebellion. The RSS has seized upon such arguments as an opportunity to mount their anti-Islamic propaganda, and have revived their old arguments regarding the rebellion as an attempt to establish an Islamic state in India. It should not be forgotten that they used the Malabar rebellion as an excuse to mount the cry of ‘Hinduism in danger’ and form Hindu protection committees in Gujarat and Maharashtra. The RSS itself was the product of such fervor. The ICHR attempt to erase the names of Malabar rebels who were eliminated and executed in the course of rebellion is a heinous attempt to obliterate the names of those who laid down their lives in the struggle against British oppression.

The ICHR act of obliteration should be seen as a continuation of the RSS assault on scientific historiography as such. The RSS has built their history on the basis of blatant lies and half-truths always embellished by the contrived, fictitious and bogus, with which they have epitomised their so-called ‘cultural nationalism’. They have been using this fraudulent history to generate their own conceptions of the nation as a Hindu nation, and to mount their attacks on the minorities, and all those critical of the RSS as anti-national. Organisations like the ICHR are busy providing fodder to the RSS anti-Muslim propaganda. By removing freedom fighters like Ali Musaliar and Variankunnath Kunjahammad Haji from the list of martyrs, they are providing the opportunity for the RSS to render these rebels as jihadists and to condemn one of the strongest movements against British imperialism as acts of perdition and debauchery by a criminal population who were called by British imperialists as ‘jungle Mappilas’. The RSS and the imperialists speak in the same voice.

The object of scientific enquiry is to discern facts from mystification, to unravel truth from a cloud of lies and distortions. Indian people have always been multi-regional, multicultural and multi-religious and have based their concept of the nation on the foundations of unity in diversity. Malabar rebellion took place in a period when organised peasant struggles based on a clear political perspective and organisational forms were only in the making, and major peasant organisations like the All India Kisan Sabha were yet to be born. Hence the rebels were forced to express themselves on the basis of their available resources, on their traditions, which may be religion, spiritualism, concepts of folk heroes and even mythology. However, it should be remembered that Khilafat, the call of the rebels did have its foundations in the existing political conditions of the period, even though it meant the restoration of the quasi-religious power of the Khalifah. Many historical studies have demonstrated the importance of such forms in the making of struggles. But this should not mislead us from the real, objective conditions that contributed to the making of such struggles, and prevent us from emphasizing their importance in making the reality of national struggle for an independent India.

Our analysis of the Malabar rebellion firmly places the struggle within the orbit of the national movement and the people who laid down their lives were definitely martyrs who fought for freedom from British oppression, and are to be remembered as such. However, this should not prevent us from losing sight of the warning given in 1946, that the conditions giving rise to the struggle also contained elements that led to its degeneration and destruction. This has to serve as a reminder for the political movement even today.