Raghu

INDIAN passenger carriers flying the highly troubled Airbus 320/321 neo (new engine option) family of aircraft with US major Pratt & Whitney 1100G engines have been given a reprieve by the Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), the aviation regulator and safety monitors. This is a high-risk move by DGCA which has put the airlines’ interest before that of the safety of air passengers who will now have to fly on problem-prone Airbus 320/321neo aircraft for several months more.

In India, Indigo and GoAir are the two Indian carriers who have 92 and 35 of these aircraft respectively in their fleet, making it 127 such aircraft in India of the total 436 operating globally. Indigo has a huge stake in the matter since it has placed orders for a whopping 730 of this family of aircraft, although it still has time to select its engine option and may be able, in future, to switch at least some orders to the CFM LEAP-1A engines made by a collaboration between General Electric of the US and Safran of France.

REPEAT PROBLEMS

AND DGCA RESPONSE

Immediate issue is that the Airbus 320 family aircraft fitted with the P&W 1100G engines have had major problems the world over but especially in India. During the three years both these airlines have operated this aircraft-engine combination, they have experienced numerous engine failures, mid-air issues requiring abrupt turnarounds back to airport of origin, and repeated groundings. Initially, DGCA chose (as it usually does, for example with the Boeing 737 MAX) to simply follow the aviation regulator of the origin-nation of the aircraft. For Airbus this is the EU Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), following whose directions, DGCA ordered complete checks of all P&W engines especially in relation to identified problem areas and, wherever problems were noticed, replace the engine with a new one while the corrective action is taken on the former. Subsequently, again following EASA guidelines, the airlines were told to replace potentially faulty engines with engines incorporating various modifications introduced by P&W (about which more later).

In April 2019, after six cases of aborted take-offs due to excessive engine vibrations, a former airline safety officer approached the Delhi High Court calling for grounding of all Airbus neo aircraft till modifications were incorporated in all of them. The Court went along with Indigo and DGCA on the latter’s assurance that it would only allow “safe aircraft” to fly. In October 2019, after Indigo experienced four mid-air engine failures requiring turnarounds and emergency landings in that month itself, DGCA directed the airlines to ensure that at least one of the two engines on each aircraft with more than 2,900 flying hours are fitted with all modified components within 15 days or face grounding. Indigo had 16 and GoAir 13 such aircraft but could not meet the target, so they were given another week. On November 1, 2019, DGCA ordered Indigo to replace all old P&W1000G engines with modified ones by January 31, 2019.

Last week, for unknown reasons, DGCA extended this deadline too by a whole five months till May 31, 2020. Even with this extended deadline, DGCA expects Indigo to have replaced only around 70 per cent of its total 135 P&W1000G engines.

Is this leniency in serial extensions of deadlines by DGCA playing with the lives and safety of passengers? Will DGCA be answerable for any untoward incident in the meantime? Was this done only to protect the interests of Indigo, who stand to lose much revenue during the peak tourist season if a large part of its fleet is grounded? Is DGCA taking refuge behind a supposed concern for air passengers who may then face higher fares and flight shortages, since Indigo today has 40 per cent market share? Safety and lives versus convenience?

Before drawing conclusions, let us understand the background.

DEMAND FOR HIGH FUEL-EFFICIENCY,

LOW EMISSIONS

Roughly in the middle of the previous decade, leading aircraft manufacturers Boeing and Airbus came out with major upgrades to their best-selling single-aisle aircraft medium-haul airliners. Boeing introduced its 737MAX which, regular readers of these columns, went through horrors due to its deeply flawed aircraft control systems, with its whole fleet grounded. Airbus introduced new engine options for its highly successful Airbus 320, 321 and 319 aircraft. Attempt of these manufacturers when design and development for these versions began about a decade earlier, was to provide greater fuel efficiency, lower emissions and noise, and improved range and load-carrying capacity. This was the aviation industry’s response to the growing clamour from the public, regulators and other national authorities, and from climate change campaigners including technical committees of the UNFCCC and ICAO, the international civil aviation industry. It should be remembered that international aviation already accounted for around 3 per cent of global emissions which were, however, kept out of global emissions control agreements.

On the airframe side, both manufacturers introduced more composite and light-weight materials, improved flight control software and systems, and innovations such as Boeing 737’s “sharklets” and Airbus’ “winglets” (the wing-tip add-ons or modifications that are today a familiar sight) to reduce drag and save 3 per cent to 7 per cent fuel.

However, most of the fuel savings, lower emissions and other improvements were to come from the engines.

The leading engine manufacturers of the world proceeded to develop the next generation of aero-engines to meet these demands. United Technologies’ Pratt & Whitney came out with its path-breaking geared turbo-fan (GTF) engine, later named P&W1100G, while its main rival, the joint venture of US-based General Electric and Safran of France (readers may recall Safran also makes engines for the Mirage 2000 and Rafale aircraft which the IAF uses or is inducting), introduced the CFM LEAP (leading edge aviation propulsion, really more a slogan than a technical description) engine incorporating major modifications to its earlier CFM56 engines, hitherto the world’s highest selling aero-engine. CFM promises 16 per cent fuel savings, while the P&W1000G promises 20 per cent or more, and both have come fairly close.

The third, albeit much smaller player, Rolls Royce of UK with its Trent engine, has also had its share of teething problems, but let us not complicate this article further.

P&W GEARED TURBO-FAN (GTF) ENGINE

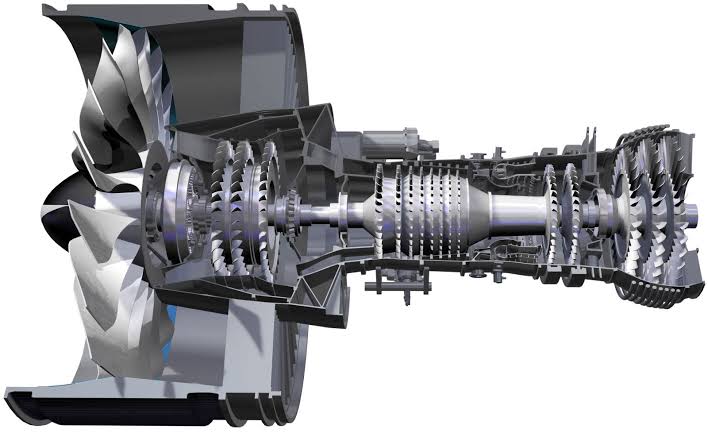

Both the CFM and P&W engines are, as is the norm these days, engines with a front fan and a high by-pass ratio for the smaller volume of air that goes through the compressor, combustion chamber and finally turbines. The idea of such an arrangement is that while the front fan, like propeller engines, accelerates a large mass of air by a comparatively small amount, the jet portion accelerates a smaller mass of air to a much greater extent, combining the fuel efficiency and power of both design concepts.

Apart from this commonality, CFM’s LEAP incorporates several novel ideas and designs, including flexible fan blades made with resins which untwist as fan speeds increase for greater efficiency, a blisk fan in its compressor (blisk = bladed disc, wherein the hub and blades are manufactured integrally rather than separately with the blades being fitted to the hub thereafter), new combustion system etc.

Pratt took the revolutionary path. It came out with a wholly novel idea, perhaps the first such completely new idea since the advent of the jet engine and later the front fan high by-pass idea. Usually, the front fan is mounted on the same shaft or spool as the compressor, with the high-pressure compressor and high-pressure turbines mounted on a second spool. P&W came up with the idea of attaching a gear to the front fan so as to enable separate control of its speed, in effect having the fan, and the two sets of compressors and turbines moving at three different speeds. It was one of those A-HA moments in engineering which left others in the aviation industry wondering why they had not thought of this simple idea themselves.

Without getting more technical, P&W had not reckoned with the several new problems that came with what appeared to be a simple new idea. Two sets of problems presented themselves. First, the response of other engine parameters, components and control systems to the new variable fan speed. Second, the new mechanical stresses that the gearing mechanism would engender.

However, P&W was also under pressure from its CFM rival and therefore rushed through its engine development process, and probably introduced it into service a few years earlier than it should have. Readers would recall that the 737 MAX too was introduced into service without ironing out its design defects especially the placement of the wings and engine mounting keeping in mind the engine dimensions, and then relied on collusion with the air safety regulator, FAA, to get the necessary approvals and airworthiness certification.

From day one, the P&W 1000G engine has been beset with problems. The new stresses especially affected the low-pressure compressor and turbine, leakages in the air seal in the third bearing, and heightened wear on the turbine. Excessive engine vibrations both at take-off and in mid-flight have also led to cracks and pieces of turbine blades braking off mid-flight and causing engine shut down. Rotor bow or bending of the rotor caused by temperature differentials along the length of the shaft led to shaft deformation, requiring dampers on the concerned shaft bearings. A redesigned piston seal in the high pressure compressor has been introduced to address transient vibration.

In the Indian cases, apart from the above problems, cooling nozzles in the combustion chamber panels frequently got blocked causing mid-air “flame outs” and engine shutdowns. P&W feels these may be due to the hot, humid, salty and polluted air over India. Leaving the last out, the other three ought to be prevalent in other countries and regions as well, such as the gulf states and south-east Asia, making one think P&W was looking for extraneous factors to blame. The air bleed system also often froze over, prompting P&W to recommend maintaining an altitude ceiling of 30,000 feet, hurting fuel efficiency.

Indigo has also been asked to modify its take-off practice of using maximum thrust, which exerts greater stress on the turbines, with Indigo recording more turbine failures than other carriers. GoAir on the other hand uses a gentler lower-thrust so-called “alt-climb” approach. While Indigo’s approach may use less fuel, it has its side effects.

Various modifications and quick-fix retro-fit solutions have been introduced, while P&W works on more permanent modifications or design changes that may take up to two years more. The main gear box too has had multiple problems, hitherto addressed by P&W through software modifications, reminiscent of the Boeing 737 Max where the basic airframe design problem was sought to be addressed by a software fix in the MCAS system.

At present, apart from the various modified seals, bearing dampers, a modified main gear box has been made mandatory along with a modified third-stage low-pressure turbine, and no engine that has been removed is accepted back from overhaul/maintenance without these.

All told, Indigo has had to replace a whopping 69 engines during 2016-18. P&W was clearly unable to keep pace as regards rapid supply of spare parts, modified parts, replacement engines etc, and Indigo too faced problems such as logistics limitations, frequent grounding of aircraft, flight disruptions, and even GST issues. Since these troubles began for Airbus with P&W GTF engines, its aircraft with CFM LEAP engines have sold 10 times more than the former, marking out a trend for the future.

IN CONCLUSION

P&W has its work cut out in the coming months and years to resurrect its reputation and that of its flagship GTF engines. Airbus may ride out the problem by relying more on the CFM engines. Both GE and Safran have sharply increased their production rate and those of their suppliers to a massive 2,000 engines a year. User airlines and Airbus are likely to look for damages from P&W.

However, the key issue for India at present is, whether the DGCA’s five-month extension to Indigo is wise. Several international commentators argue that it is, given the experience of other operators. Whatever the reason, including tardy supply of spares and modified parts by P&W, the fact remains that passenger safety, even their lives, are put at risk whenever Airbus320s with unmodified P&W engines fly, given the multiple problems the engine has faced.

DGCA would be well-advised to err on the side of caution, and is playing a high-risk game with this extension. The least that DGCA can do is to require both Indigo and GoAir, as well as all travel agents and booking sites and aggregators, to indicate prominently each flight of these two airlines where one or both P&W engines are unmodified. Right now there is no such indication and passengers are neither alerted to a possible problem nor has there been a well-publicised advisory by DGCA. At the very least, passengers should be made aware of the risks involved so that they can take an informed decision.

This author has, till such measures are taken by DGCA, recommended to everyone he knows not to fly Indigo or GoAir till these problems have been resolved or more information is provided to passengers.