A Reporter

‘SEASONS come and go – as do governments – and currently Delhi is witnessing a particularly cold spell.’ When the noted poet and lyricist Javed Akhtar said this, an ostensible statement about the weather became a poetic barb at the ruling dispensation. He was addressing hundreds of workers and their families on January 1, 2020, at the site of Safdar Hashmi’s killing at Jhandapur in the Sahibabad Industrial Area on the outskirts of Delhi. ‘But one season doesn’t change, for the poor – the season of exploitation and oppression.’

It is this ugly reality that the rulers want to hide. The poor don’t have food to fill their stomachs, they don’t have jobs for their children, medical care for the aged, but none of this matters. ‘The rulers tell us that we must have pride (‘garv’) in our religion. They don’t give us jobs, they don’t give us food, they don’t give us medical care, all they give us is pride. Why?’

Because, Akhtar continued, they want us to continue thinking of ourselves in terms of vertical identities – Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, Parsi, Christian, etc. They don’t want us to think of ourselves in terms of horizontal identities – the super rich, the very rich, the rich, the middle class, the lower middle class, the poor, the destitute. These horizontal identities are dangerous to them, because then they wouldn’t be able to continue the eternal season of exploitation. They want to turn India into a Hindu Pakistan.

It is the poor, Akhtar said, who are going to suffer the most with the CAA – not only Muslims, but all the poor. The rich, whether Muslim or Hindu, will find a way, but the poor will be effectively disenfranchised. It is the votes of the poor that have carried the current dispensation to power, and now they want to disenfranchise the very people who gave them power. This needs to be resisted with all might.

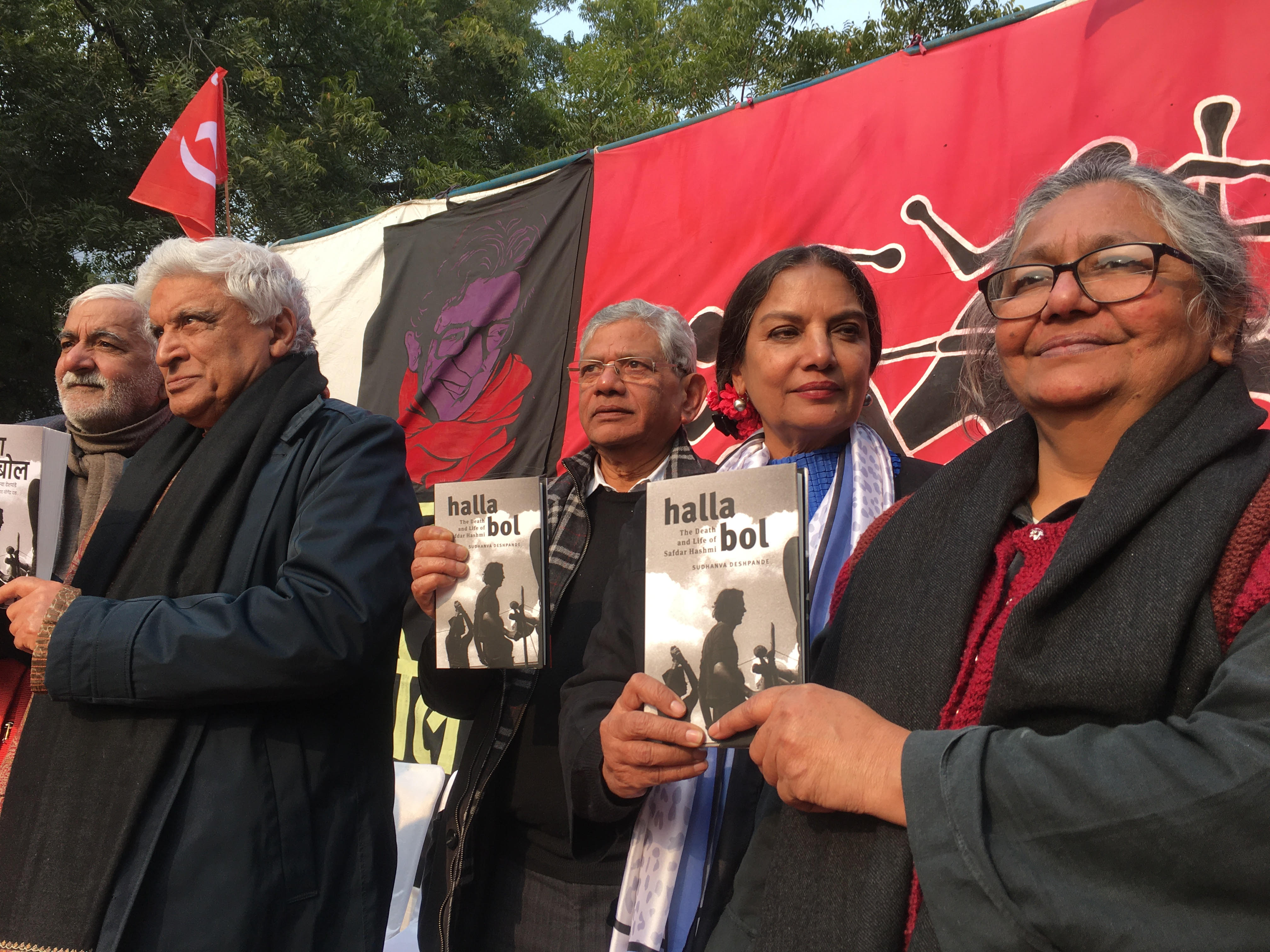

Along with noted actress Shabana Azmi, Akhtar was in Sahibabad to release a new book: Sudhanva Deshpande’s HallaBol: The Death and Life of Safdar Hashmi, published in Hindi and English by Vaam Prakashan and LeftWord Books. The presence of Shabana Azmi made the occasion special and resonant. Exactly one week after the attack that resulted in the death of Safdar Hashmi, Azmi, in a stirring act of courage, had read out a protest note from the stage of the International Film Festival in New Delhi. It was an electrifying moment, and had energised the protests that followed the killings.

Being in Jhandapur to release the book, Azmi said, was special to her, both because it was about Safdar, and because it reminded her of her own childhood, when her father, the legendary Communist poet Kaifi Azmi – whose birth centenary is also being celebrated this year – would carry her to workers’ gatherings in Mumbai. To be in Jhandapur, she said, was truly energising and inspiring.

For the past 31 years, Jhandapur has been the site of a unique coming together of workers and artists. It was at this exact spot that Jana Natya Manch and CITU were attacked by Congress-supported goons on January 1, 1989. A worker, Ram Bahadur, was shot dead, and the artist Safdar Hashmi, leader of Jana Natya Manch, was grievously injured. He died of head injuries in a New Delhi hospital the next day, on January 2. He was 34 years old. The next day, January 3, witnessed an unprecedented outpouring of anger and rage, as over 15,000 people took part in Safdar’s funeral procession.

Less than 48 hours after Safdar’s death, on the morning of January 4, 1989, Jana Natya Manch, led by Moloyashree Hashmi, went back to the site of the attack and completed the play that had been interrupted because of the attack. Janam’s performance was an incredible act of commitment to the people. It was also a way of saying that violence can silence individuals, but not the collective.

The attack itself was in response to what is the largest single action of working class militancy in the history of Delhi’s trade union movement – the historic Seven-day strike of November 1988, when 1.3 million workers across Delhi, Ghaziabad and Faridabad struck work. Jana Natya Manch had prepared a play in support of the strike, and had performed it at multiple locations as a lead-up to the strike. After the strike, a reworked version of the play, entitled Halla Bol (Raise Hell), was prepared by the group, and it was this play that was being performed on January 1, 1989. It is fitting, therefore, Sudhanva Deshpande’s book on Safdar Hashmi is also titled after this play.

CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury was a close friend of Safdar’s. Yechury reminiscenced warmly about his friend in the public meeting in Jhandapur on January 1, 2020. He recalled how as a young student activist, he first met Safdar and the two spent countless hours together in the company of other comrades. Then, Safdar took up a teaching job first in Garhwal and then in Kashmir, for about two years. When he came back to Delhi, coincidentally, the Left Front government of West Bengal was seeking to set up an Information Bureau. Buddhadev Bhattacharya, who was then information minister, asked Yechury if he would think of someone who could take that job. Yechury suggested Safdar’s name, and thus it came about that for about three years, Safdar Hashmi served at the West Bengal Information Bureau in New Delhi. During this time, he turned the Bureau into a vital cultural space, and helped create a favourable atmosphere for the Left Front government in Delhi.

In their friendship, Yechury, recalled, it never occurred to either of them what names they carried and which communities those names denominated. ‘We never thought of “I” or “me”, we always thought of “us” – “hum”. And it is to be noted that the two sounds that make up this “hum” – “H” and “M” – stand for the two largest communities in India.” Yechury lambasted the Modi government for trying to create a wedge in this ‘Hum’ through the unconstitutional Citizenship (Amendment) Act. The CPI(M) and the Left will resist this with all the force at their command, he said.

Yechury recalled Safdar’s commitment to the working class and its struggles and said that his killing was a huge loss to the movement, but also that his life is an inspiration to activists. Safdar’s commitment to working class has been a touchstone of Jana Natya Manch’s work over the decades. Its latest play, Unsune Afsane (Untold Stories) is testament to this commitment. Set in the industrial landscape of Delhi, the play is a moving tale of the tragic death of a worker, and how it galvanises an older woman worker towards struggle. The play, with shades of Maxim Gorky’s novel Mother and Bertolt Brecht’s play of the same name based on the novel, is a tight, well-crafted piece which makes innovative use of sound and visuals. Directed by Komita Dhanda, the play is being performed as part of CITU’s preparations for the all-India strike of January 8, 2020.

Since Safdar died on January 2, Jana Natya Manch observes this day every year with a small, intimate meeting of its members in which they remember their comrade. This year, this meeting was addressed by veteran activist of the writers’ movement, Rekha Awasthi, along with Janam members Brijesh and Ravi.

Earlier in the day, Shabana Azmi and Javed Akhtar visited Studio Safdar and May Day Bookstore in Shadipur in west Delhi. Both spaces were set up in 2012, and are inspired by Safdar’s dream of setting up a cultural centre in a working class area. That dream was never fulfilled in his lifetime, but Janam realised it later, with the help of contributions from hundreds of artists, activists, and others. Shabana Azmi had contributed significantly to the venture with a personal contribution as well as donating the proceeds from a play she was acting in at the time. It was therefore a special occasion for Janam to host her at the space and to talk about all the work that Studio Safdar has been doing over the past eight years.

The tribute to Safdar culminated with a poetry reading session organised by Janam on January 3.