THROUGH Bismarck’s Emergency Laws against, the Socialist German Workers, movement, the route to the Karlsbad water cure, which had done Marx so much good, was barred to him. From 1878 on his physical suffering grew worse again and hindered him increasingly in his work. But he was not the man to give in to illness and pain. In this sense also he fought to the end.

With the smallest improvement in his health he returned to his work again. Summoning all his strength, he attempted to prepare the second book of Capital for the printer. But his efforts were repeatedly thwarted by almost unendurable headaches, torturous coughing, nerve inflammation and attacks of weakness. These were years of quiet but heroic struggle, and the manuscript of this period, as Engels later said all too often showed traces of an intense struggle against depressing ill health. Despite his iron will, Marx was no longer able to complete the final draft of the second and third volumes of Capital for publication.

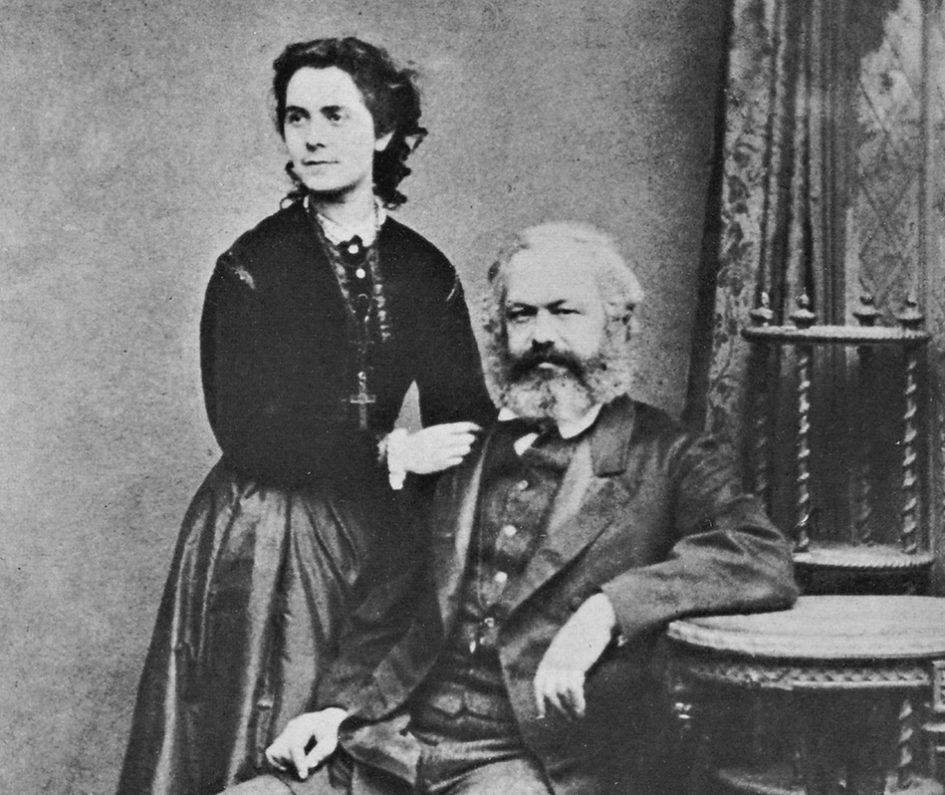

LAST YEAR OF JENNY’S LIFE

His wife’s suffering tortured Marx almost more than his own. After a long uncertainty, it was established that her illness, presumably cancer of the liver, was incurable. Jenny bore the terrible pains with astonishing patience and still retained her cheerfulness. Filled with pain, but not discouraged, she wrote to a doctor: “I clutch at every straw. I want so very much to live a little longer, dear, good doctor. It is remarkable: the more one’s story approaches the end, the more one yearns for the ‘earthly vale of tears.”

In the last year of her life, unbowed, she followed with great interest every advance of the workers’ movement in the various countries. It was a great joy for her as well as for Karl to be able to receive August Bebel at their home at the end of 1880. Bebel had journeyed to the two “old men” in London to inform them about the public and internal situation in the German party. He consulted with them on the tactics of the party and got their agreement to write for Der Sozialdemokrat. Marx and his wife, as well as Engels, were very much impressed with this wise, energetic leader of the working class of Germany, who was so closely connected with the masses, and they had for so many years known only through correspondence. Marx immediately addressed him with the brotherly “du” and thirty years later Bebel was still moved when the reported on his visit to the Marx home :

“On the single Sunday that we spent in London, we were all invited to Marx’s table. I had already become acquainted with Frau Jenny Marx. She was as distinguished woman who immediately won my sympathy, and who understood how to entertain her guests in the most charming, the most lovable manner. On that Sunday I also met the eldest daughter Jenny, married to Lounguet, who had come on a visit with her children. I was very pleasantly surprised to see with what warmth and tenderness Marx, who was at that time denounced everywhere as the worst enemy of mankind, played with his two grandchildren, and what love they had for their grandfather. Apart from Jenny, the eldest daughters, the two younger daughters, Tussy, later the wife of Aveling and Laura, the wife of Lafargue, were also present. Tussy, with black eyes, resembled her father, and Laura, light blonde, with dark eyes, more the picture of her mother… both pretty and lively.”

When Bebel came to say good-bye on the next day, Marx’s wife was in bed, struck down again by pain. These were terrible months. Marx did not move from his wife’s side. To give her pleasure, he arranged a trip with her to France in July and August 1881, to visit their eldest daughter and their grandchildren. When they returned home Jenny was completely exhausted.

BITTEREST BLOW TO MARX

Worn out by anxiety and sleeplessness, Marx contracted a severe case of pneumonia in the autumn of 1881. Only the self sacrificing care of Eleanor and Lenchen Demuth helped him recover. “Never”, Eleanor wrote of the last days Karl and Jenny spent together, “will forget the morning on which he felt strong enough to go to mother’s room. They were young again, together she a loving girl and he a loving youth who were starting out in life, and not an old man shattered by illness and a dying old woman who are taking leave of each other forever.”

There were still a few joys left for Jenny. From Germany came the news that a third edition of Capital had become necessary. And in England, for the first time, an article appeared in a leading publication that lauded Marx as a significant scientist and Socialist thinker. And the German Workers’s movement showed, through an imposing electoral success at the end of October, that it was fighting on unbroken despite the Emergency Laws and was becoming increasingly imbued with Marx’s teachings.

ENGELS TRIBUTE

Jenny died on December 2, 1881. It was the bitterest blow Marx had ever had to endure. He could not even accompany his beloved wife to her resting place. The doctors, concerned about his weakened condition, did not allow him to take part in the funeral service at Highgate cemetery. At the grave, Engels spoke about Jeeny’s love for her husband and her family, her helpfulness to friends and comrades, her loyalty to the struggle for the international proletariat. He closed with these words: “what such a woman, with such a sharp and critical understanding, with these words: “What such a woman, with such a sharp and critical understanding, with such passionate energy, such a great capacity for devotion—what such a woman has contributed to the revolutionary movement has never emerged into the public view, has never been mentioned in the columns of the Press. What she did is known only to those who lived with her…

“I do not have to speak of her personal traits. Her friends know these, and will never forget them, If there was ever a woman who saw her own happiness in making others happy, then it was this woman.”

Karl Marx could not overcome the death of his wife. “The Mohr has also died.” Engels said with truth on the day that Jenny passed away. But his great will to live rose up once more. He was determined to conquer the bothersome illness that doomed him to inactivity. “I will unfortunately have to lose some time with manoeuvres to get back on my feet again,” he wrote discontendly to his old friend Sorge in the USA.

TRIP TO ALGERIA

On the advice of his doctors Marx sought to revive in the months that followed in areas with a milder climate. First he went to Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. In the spring of 1882 he traveled to Algiers. But the pain of being without Jenny followed him every-where. He wrote movingly to Engels: “By the by, you know that few people (are) more averse to demonstrative pathos; still, it would be a lie (not) to confess that my thoughts (are) to great part absorbed by reminiscences of wife… the best part of my life.”

Yet even in these weeks, though seriously ill, he utilised every opportunity to learn something new. In Algiers, he found in a friend of his son-in-law, Longuet, someone who was able to give him important and detailed information about the refined and gruesome forms of colonial oppression to which the Arabs were subjected. With equal attention, though from news about the European workers’ and continued his exchanges of views with Engels, once again, as earlier, in the form of letters.

The Algerian trip brought no improvement in his health: neither did the stay in the south of France that followed. Only later, when visiting his daughter Jenny in the vicinity of Paris and then in late summer in Switzerland, did he slowly feel somewhat better. In the meantime the news of death of Bebel caused him deep agitation. He wrote to Engels: “It is shocking, the greatest misfortune for our party. He was a unique personality within the German (one can say within the ‘European’) working class.” Fortunately, the news was soon shown to be false.

DAUGHTER’S DEATH

In October, Marx returned to England, physically stronger. He was already thinking of resuming his work on Capital again and helping the party organ Der Sozialdemokrat, with articles. But the improvement in his health was only short-lived. To escape the November fog of London he went again to Ventnor, but the dampness and cold weather of the winter bothered his ailments there also. Worse still, he received another terrible blow; the news of the death of his daughter Jenny. Eleanor, who brought him the tragic news, wrote :

“I have had many sad hours in my life, but none so sad as these.” She knew what Jenny’s death would mean for him. “I felt that I had brought my father the sentence of death. On the long, fearful trip I racked my brains as to how to give him the news. I didn’t have to report it to him; my face betrayed everything. Mohr said at once: Our Jennychen is dead! And them he immediately instructed me to go to Paris and help with the children.”

DEATH IN SLEEP

On the next day Marx returned to London. A broachial condition to which an inflammation of the larynx was soon added forced him to take to his bed. For weeks he could only take liquid foods. In February, he developed a lung abscess.

In March hopes rose for his recovery. With Lenchen’s tender nursing, the main ailments were almost better. But Marx’s appearance was deceptive. On the afternoon of March 14, Engels, who visited his friend daily during this period, came to the house. Lenchen met him and said Marx was holy asleep. “When we entered the room,” he wrote later to Sorge, “he was lying there asleep, but never to wake again. His pulse and breathing had stopped. In those two minutes he had passed, peacefully and without pain.”

Engels added: “Mankind is shorter by a head, and that the greatest head of our time. The movement of the proletatriat goes on. But gone is the central point to which Frenchmen, Russians, Americans and Germans spontaneously turned at decisive moments to receive always that clear, indisputable counsel which only genius and consummate knowledge of the situation could give.”

The workers of the whole would mourned with Engels. On March 17, 1883, Karl Marx was laid to rest beside his wife to the Highgate Cemetery.

The international workers’ movement took farewell of its great leader, and at his grave Wilhelm Liebknecht pledged in the name of the working class of Germany.

“Instead of mourning, we will act in the spirit of the great departed. We will strive with all our strength to make a reality as quickly as possible of what he taught us and aspired to. In this way will we best celebrate his memory.

“Dear dead friend! We will march along the road that you showed us until the end. We swear it on your grave!”