Sitaram Yechury

NELSON Mandela is no more. When my generation was in its teens, a popular song went as follows: 'To dream the impossible dream/To fight the unbeatable foe/To bear with unbearable sorrow/To run where the brave dare not go/To right the unrightable wrong.../To reach the unreachable star/This is my quest/To follow that star/No matter how hopeless/No matter how far...'

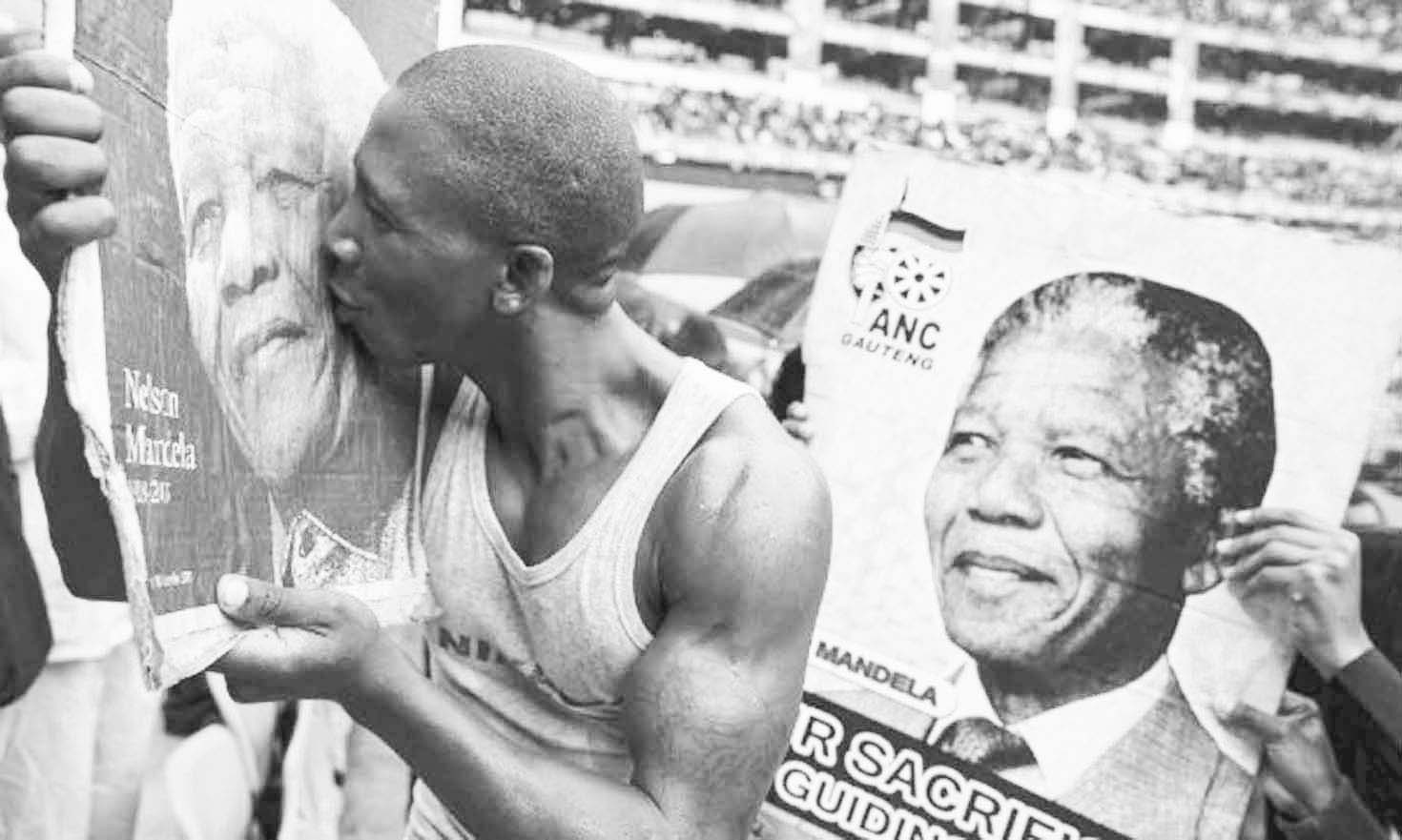

If there is one person who lived up to these ambitions and more importantly reached these milestones in his own lifetime, it was Nelson Mandela, Madiba as he was fondly called.

His political life and work is indeed well documented and hence needs no repetition. His times and contribution have been documented by his comrades-in-arms, like Ahmed Kthrada and others and these will surely be enriched and refined further in the future.

As my generation grew up, Mandela symbolised the unquenchable human spirit for freedom and liberty. As a teenager, he organised the youth wing of the African National Congress (ANC) and went on to become the first chief of the ANC armed wing Umkhonto We Sizwe – spear of the nation. He was a passionate fighter against the hated apartheid regime that denied the South African people their elementary human rights while oppressing them mercilessly. He was arrested and in what had became the famous Rivonia trial, was sentenced for imprisonment for life. Concluding his testament at the trial, he stated: “During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die”. (June 11, 1964)

He was offered conditional releases on six occasions during his long detention in the notorious apartheid prison in the Robben Island. He refused each one of them and on last occasion, while refusing said: “What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? What freedom am I being offered when I may be arrested on a past offence? What freedom am I being offered to live my life as a family with my dear wife who remains in banishment in Brandfort? What freedom am I being offered when I must ask for permission to live in an urban area? What freedom am I being offered when I need a stamp in my pass to seek work? What freedom am I being offered when my very South African citizenship is not respected? Only free men can negotiate...I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free”.

Such was his indomitable spirit that explains his enduring inspiration.

His eventual release came when the whole world realised, ironically including those ardent supporters of the oppressive regime, that the apartheid system had become an anachronism in the modern world. As the Cold War was coming to an end, an objective that appeared impossible a few years earlier was also approaching its end – the destructive apartheid system and freedom for the people of South Africa. For our generation there was a lesson to be learnt – history always unfolds in contradictory terms. The crisis that was about to engulf the world, with the dismantling of the socialist Soviet Union and the end of the countervailing military and economic bulwark to imperialist hegemony was accompanied by the release of Mandela and freedom from bondage for the peoples of a large part of the African continent. The wisdom of the ancient Chinese saying, that 'every crisis encompasses an opportunity', appears true.

I had the opportunity of meeting Nelson Mandela thrice. The first, was on the occasion of the 48th Congress of the ANC, the first since its banning in 1960 to be held on South African soil in July 1991 at Durban. The atmosphere was indeed an experience of lifetime. Comrades separated from each other, imprisoned in solitary confinement for more than three decades were meeting each other for the first time, struggling to recognise each other as all had grown old. Many tragically ceased to exist. The city of Durban still continued with the trappings of apartheid segregations, with its famed beaches splattered with hoardings: 'Non-Whites and Dogs – Out of Bounds'. While there was euphoria that apartheid was ending, Mandela however struck a note of caution when he spoke to the Congress saying: “We have suspended armed action, but have not terminated the armed struggle. Whether it is deployed inside the country or outside, the Umkhonto We Sizwe has therefore a responsibility to keep itself in a state of readiness in case the forces of counter-revolution once more block the path of a peaceful transition to a democratic society. It is precisely that struggle which has changed the balance of forces to such an extent that the apartheid system is now under retreat. Through the struggles of our people the ban on the ANC has been lifted and we are able to meet in our own country today. A regime whose ideology is based on a virulent anti-communism has been forced to unban our ally the South African Communist Party (SACP), and remove provisions from the law prohibiting the propagation of communist ideals”.

One of the main charges against Mandela, which led to his arrest was that he was a communist. Indeed, he was a member of the central committee of the SACP once, before his arrest. In the period of the collapse of the Cold War, alignment with the frenzy of anti-communism in the air, such charges were once again levelled against free Mandela as a warning by the imperialist West. He answered such an ideological offensive at the massive public rally at the conclusion of this Congress by saying: “who are your allies is your business and who are our allies is our business”.

I met Mandela once again, in December the same year on the occasion of the Eighth Congress of the SACP, where Mandela's successor as the chief of Umkhonto We Sizwe, Chris Hani was elected as the Party general secretary. Comrade Hani was subsequently assassinated by the counter-revolutionary apartheid forces. By then, Mandela with the resilience of a visionary had come to the conclusion that the South African population had suffered more than what a human being was capable of and hence peace was the most required objective. He had proposed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a method to stave off continued conflict and perpetuation of violence as the reactionary colonialists continue to be superiorly armed. This apparent gesture for peace and reconciliation tempered the bitterness and the sense of revenge that many rightfully harboured. There were many sceptics who saw in this an element of passivity. Mandela, however warned the SACP and the tripartite alliance partners, ANC and COSATU partners that they should never lower their guard against the possible armed retribution by the enemy. For Mandela, therefore, 'non-violence' was more of a tactic than what is often misunderstood as the Gandhian strategy. Incidentally at Durban, it was he who first told me that we from India had sent Mohandas to South Africa and they returned the Mahatma to India.

The last occasion that I met him was at the SACP 10th Congress at Johannesburg in July 1998. Mandela had voluntarily stepped-down and handed over the presidency of the Republic to Thabo Mbeki, a move that was accepted by the people of South Africa with widespread dismay. He was probably the only African leader to have ever done so. The only other person that I can recollect having done a similar thing was Jyoti Basu, when he voluntarily stepped-down as the chief minister of West Bengal.

Jyoti Basu and Mandela shared a very unique relationship. On Mandela's first visit to India, he insisted on visiting Calcutta and was moved to tears. He told the roaring crowds: “The welcome accorded to us in the streets of this city today, convinces us that we have come home, and that here we are among fellow revolutionaries...Your heroes of those days became our heroes. Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose was indeed among the great persons of the world whom we black students regarded as much our leader as yours...I am full of strength and hope after visiting Calcutta. I feel like a man with his batteries recharged”. (October 1990)

At the SACP 10th Congress, Mandela was intensely engaged with the debate which centred round the economic policies being followed by the ANC government that came under severe criticism and correctly so, by the communists. The economic policies were integrating South Africa more and more into the neoliberal order of imperialist globalisation, while the promises of liberation for the people continued to remain a distant possibility. The SACP had threatened the Mbeki government that while they continue to be part of the ruling tripartite alliance, they shall play the role of a 'watchdog' and not that of a 'lapdog' of such government policies. This in fact reflects the unsolved legacy of the South African liberation movement. Much as Mandela would have liked to have seen, far reaching radical land reforms that were essential to empower the impoverished black population economically, they are yet to see the day. This objective continues to remain as the original ANC Freedom Charter and the agenda of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR). The levers of economic power, continue to remain in the hands of the former colonial masters or the small black bourgeoisie that has now emerged as their collaborators. This remains the unfinished agenda which Mandela could not see to its fruition in his lifetime. In essence this is a task that he had bequeathed to the current generation and the future to resolve at the earliest. The SACP 10th Congress slogan: “Future is Socialism” is an ongoing struggle to be realised.

Notwithstanding this, Nelson Mandela, strode like a colossus in humanity's quest for scaling ever higher peaks, constantly pushing higher the bar that defines human liberty and freedom as the song that we began with ends...'Still strove with his last ounce of courage/To reach the unreachable star'.

Nelson Mandela - Timeline

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (July18, 1918 – December 5, 2013) was a revolutionary, anti-apartheid leader, who served as president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the first elected in a democratic election. He was instrumental in dismantling apartheid by tackling institutionalised racism and fostering racial reconciliation. Ideologically, Mandela was an African nationalist and socialist, he served as president of the African National Congress (ANC) party from 1991 to 1997.

Important phases in Nelson Mandela’s life span:

- Mandela was born on July 18, 1918 in Mvezo, British South Africa.

- He studied law at the University of Fort Hare and the University of Witwatersrand. Mandela practiced law in Johannesburg.

- Joined the ANC in 1943.

- Co-founded its Youth league in 1944.

- Mandela was appointed president of the ANC’s Transvaal branch owing to his rise in prominence for his involvement in the 1952 Defiance campaign and the 1955 Congress of the People.

- He was repeatedly arrested during that period for ‘seditious activities’ and was unsuccessfully prosecuted in the 1956 Treason trial.

- Mandela was influenced by Marxism; he secretly joined the banned South African Communist Party (SACP).

- He co-founded with the SACP, the militant wing-Umkhonto we Sizwe in 1961. This led to a ‘sabotage’ campaign against the government.

- In 1962 he was arrested for conspiring to overthrow the state in the famous Rivonia trial.

- The Rivonia trial continued from October 9, 1963 to June 12, 1964.

- The trial led to the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela and others who were convicted of sabotage and sentenced to life at the Palace of Justice Pretoria.

- Mandela served 27 years in prison (from 1962), split between Robben Island, Pollsmoor Prison, and Victor Verster Prison. In Robben Island he was imprisoned for 18 years.

- In the year 1990, Nelson Mandela was released amid growing struggles of the people in South Africa and international pressure, and with fears of a racial civil war.

- Efforts of Mandela and de Klerk led to negotiating an end to apartheid which resulted in the 1994 multiracial general elections.

- Mandela was awarded the Noble Peace Price along with de Klerk. Mandela received more than 250 honours from the international community including Bharat Ratna – India and Order of Lenin –USSR.

- The apartheid was officially ended and Mandela led the ANC to victory in 1994 and became the president of South Africa.

- Mandela led a broad coalition government, which promulgated a new constitution.

- He emphasized reconciliation between the country’s racial groups and created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate past human rights abuses.

- Mandela continued president till 1999 and declined a second presidential term. Thabo Mbeki succeeded him as the president of South Africa.

- In 1999 Mandela founded a charitable ‘Nelson Mandela foundation’ trust, to promote his vision of freedom and equality for all.

- He is held in deep respect within South Africa, where he is often referred to by his Xhosa clan name, Madiba, and described as the "Father of the Nation".

- Mandela breathed his last on December 5, 2013.