R Arun Kumar

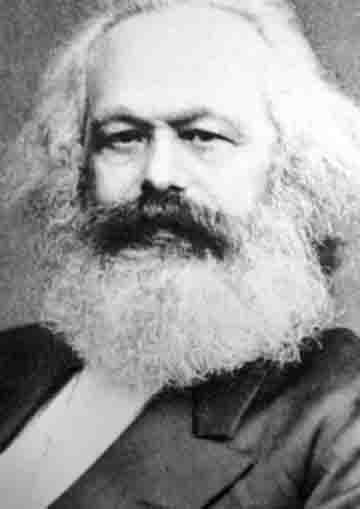

IN another two years, the world will be observing the 200th birth anniversary of Karl Marx, who was born on May 5, 1818. Hailed as the greatest thinker of the millennium, Marx had an enormous impact on the world and hence it is not an exaggeration to say that his bi-centennial birth anniversary will be observed by the entire world. Marx is one such personality, whom you can either love or hate, but can never ignore.

Marx's thought and analysis influenced and continues to influence not only various branches of social sciences – history, economics, sociology, philosophy, political science, gender studies, anthropology, etc – but also literature and various other disciplines of natural sciences too. Frederick Engels, lifetime friend and comrade-in-arms of Karl Marx, speaking at the grave of Marx after his death on March 14, 1883, at the age of 64, stated that “the greatest living thinker ceased to think”. Further explaining the greatness of Marx, Engels proceeded: “...in every single field which Marx investigated – and he investigated very many fields, none of them superficially – in every field, even in that of mathematics, he made independent discoveries. Such was the man of science. But this was not even half the man. Science was, for Marx, a historically dynamic, revolutionary force. However great the joy with which he welcomed a new discovery in some theoretical science whose practical application perhaps it was as yet quite impossible to envisage, he experienced quite another kind of joy when the discovery involved immediate revolutionary changes in industry, and in historical development in general”.

It is not out of innocent curiosity that Marx had shown interest in all these varied fields of sciences. Marx developed this interest with a purpose, which Engels succinctly points out: “Marx was before all else a revolutionist. His real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the State institutions which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat, which he was the first to make conscious of its own position and its needs, conscious of the conditions of its emancipation. Fighting was his element”. Thus, emancipation of humankind, with proletariat as the driving force of the revolution, motivated the endeavors of Marx.

Lenin, one of the ablest practitioners of Marxist thought states, “The Marxist doctrine is omnipotent because it is true. It is comprehensive and harmonious, and provides men with an integral world outlook irreconcilable with any form of superstition, reaction, or defence of bourgeois oppression. It is the legitimate successor to the best that man produced in the nineteenth century, as represented by German philosophy, English political economy and French socialism”. Hailing the genius of Marx, Lenin states that Marx was the 'first to deduce the lesson world history teaches' – the doctrine of the class struggle – 'and to apply that lesson consistently'.

Sharpening of class struggles for the revolutionary transformation of the society is the crux of all the activities that had guided Marx throughout his lifetime. These ideals determined his analysis of various important developments that had taken place during his life period – the revolutions of 1848, that took place in many European countries and the Paris Commune of 1871. He gave enormous importance to practice and put his analysis to test intervening in the various proletarian actions during that period.

Fresh from drafting the 'Communist Manifesto' at the age of 30 in 1848, Marx got an opportunity to test his ideas in the revolutions that shook Europe that year. Though proletariat participated in these revolutions, they were basically bourgeois-democratic revolutions and socialist revolution was nowhere on the agenda, except in France. The cowardly nature of the bourgeoisie led it to compromise with the reactionary forces and led to the birth of a 'stillborn democratic revolution'. In many countries, monarchies transformed themselves into constitutional monarchies, granting semblance of rights to the people.

Commenting on the activities of Marx and Engels during this period, Lenin stated: “in the activities of Marx and Engels...the period of their participation in the mass revolutionary struggle of 1848–49 stands out as the central point. This was their point of departure when determining the future pattern of the workers’ movement and democracy in different countries”.

In the elections held in 1849, initially Marx and Engels had advocated that proletariat vote for the liberal bourgeois democrats as the party of the worker-peasant and petty-bourgeois alliance was not strong enough. But subsequently, self-critically examining this position and noting the betrayal of liberal bourgeoisie, they changed their position stating that “petty, crafty liberal slyness was never the diplomacy of revolutionaries”. Elaborating on the tactics that the working class party has to pursue, particularly in its dealings with the petty-bourgeois democrats during the course of democratic revolution, they stated: “(T)hat everywhere worker’s candidates are put up alongside the bourgeois-democratic candidates, that they are as far as possible members of the League, and that their election is promoted by all means possible. Even when there is no prospect whatever of their being elected, the workers must put up their own candidates in order to preserve their independence, to count their forces and to lay before the public their revolutionary attitude and party standpoint. In this connection they must not allow themselves to be bribed by such arguments of the democrats as, for example, that by so doing they are splitting the democratic party and giving the reactionaries the possibility of victory. The ultimate purpose of all such phrases is to dupe the proletariat. The advance which the proletariat party is bound to make by such independent action is infinitely more important than the disadvantage that might be incurred by the presence of a few reactionaries in the representative body” (Emphasis added).

Here, Marx and Engels categorically state that electoral victories are subordinate to independent working class action, the prime task of a working class party is to 'count their forces and to lay before the public their revolutionary attitude and party standpoint', not to get duped by the arguments of so-called democrats and prioritise on the advance of independent action. These, according to them, outweigh the risk of reactionaries getting elected.

Both Marx and Engels were unsparing in their criticism of those who considered getting elected to parliament as more important than developing independent working class actions and building the strength of the party on that basis. Engels wrote: “These poor, weak-minded men, during the course of their generally very obscure lives, had been so little accustomed to anything like success, that they actually believed their paltry amendments, passed with two or three votes’ majority, would change the face of Europe. They had, from the beginning of their legislative career, been more imbued than any other faction of the Assembly with that incurable malady, parliamentary cretinism, a disorder which penetrates its unfortunate victims with the solemn conviction that the whole world, its history and future, are governed and determined by a majority of votes in that particular representative body which has the honor to count them among its members, and that all and everything going on outside the walls of their house – wars, revolutions, railway-constructing, colonizing of whole new continents, California gold discoveries, Central American canals, Russian armies, and whatever else may have some little claim to influence upon the destinies of mankind – is nothing compared with the incommensurable events hinging upon the important question, whatever it may be, just at that moment occupying the attention of their honorable house”.

Marx vehemently opposed any attempts to use the International as a means to achieve parliamentary ambitions. “I regret saying, most of the workmen’s representatives use their position in our council only as a means of furthering their own petty personal aims. To get into the House of Commons by hook or crook, is their ultima Thule (most cherished goal), and they like nothing better than rubbing elbows with the lords and MP’s by whom they are petted and demoralised”.

Marx and Engels made it absolutely clear that their positions should not be construed to mean that they were against participation in elections, absenteeism. “The political domination of the proletariat...revolution is the supreme act of politics; whoever wants it must also want the means, political action, which prepares for it, which gives the workers the education for revolution and without which the workers will always be duped...But the politics which are needed are working class politics; the workers’ party must be constituted not as the tail of some bourgeois party, but as an independent party with its own objective, its own politics. The political freedoms, the right of assembly and association and the freedom of the press, these are our weapons – should we fold our arms and abstain if they seek to take them away from us? It is said that every political act implies recognition of the status quo. But when this status quo gives us the means of protesting against it, then to make use of these means is not to recognise the status quo”. (Emphasis added)

Even here they emphatically state that what is needed is working class politics, maintaining the independent positions without becoming the 'tail of some bourgeois party'. Participation in parliaments is, for them, a means to an end – a platform to propagate revolutionary principles and further the cause of revolution.

Marx writing to a longtime friend in Germany about the harmful tendencies that are cropping up in the Party, laments: “In Germany a corrupt spirit is asserting itself in our party, not so much among the masses as among the leaders (upper class and ‘workers’). The compromise with the Lassalleans has led to further compromise with other waverers...not to mention a whole swarm of immature undergraduates and over-wise graduates who want to give socialism a ‘higher, idealistic’ orientation, i.e. substitute for the materialist basis...a modern mythology with its goddesses of Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternité”.

Criticising Bernstein and others for their opportunism and revisionist ideas, where they wanted the party to abandon its proletarian orientation, make an appeal to both the petit bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie, and adopt a less threatening posture toward Bismarck’s regime, Marx and Engels had written a letter to the party members, called the Circular Letter. “Therefore elect bourgeois! In short, the working class is incapable of emancipating itself by its own efforts. In order to do so it must place itself under the direction of ‘educated and propertied’ bourgeois who alone have ‘the time and the opportunity’ to become conversant with what is good for the workers. And, secondly, the bourgeois are not to be combatted – not on your life – but won over by vigorous propaganda”.

Further, the goal of the 'trio', was “to relieve the bourgeois of the last trace of anxiety” by showing it “clearly and convincingly that the red spectre really is just a spectre and doesn’t exist...They accept it (the Party programme) – not for themselves in their own lifetime but posthumously, as an heirloom for their children and their children’s children. Meanwhile they devote their ‘whole strength and energies’ to all sorts of trifles, tinkering away at the capitalist social order so that at least something should appear to be done without at the same time alarming the bourgeoisie”. (Emphasis added)

Arguing that such people should be immediately made to leave the party, Engels wrote: “they (the trio) think as they write, they ought to leave the party or at least resign from office (the editorial committee). If they don’t, it is tantamount to admitting that they intend to use their official position to combat the party’s proletarian character. Hence, the party is betraying itself if it allows them to remain in office”. Engels stating that “Under no circumstances should they be permitted to be in the leadership of the SAPD”, sarcastically asked Bernstein and his comrades to form their own party, a 'Social-Democratic petty-bourgeois party' separate and apart from a 'Social-Democratic Workers’ Party'. (Emphasis added)

For Marx and Engels victory in elections was always secondary. Engels told Bebel, “I am less concerned just now with the number of seats that will eventually be won...the main thing is the proof that the movement is marching ahead...and the way our workers have run the affair, the tenacity, determination and above all, humor with which they have captured position after position and set at naught all the dodges, threats and bullying on the part of the government and bourgeoisie”. Commenting about the successes in the 1887 elections, he said, “But it’s not the number of seats that matter, only the statistical demonstration of the party’s irresistible growth”. Remarking on the 1893 elections, he reiterated, “The number of seats is a very secondary consideration” as for him that which is of significant importance is of using the electoral arena to 'build the worker-peasant alliance'. All tactics, they repeatedly urged, should dovetail to ensure the ascendancy of working-class and for this purpose, it is necessary to build the worker-peasant alliance. (Emphasis added)

Marx and Engels painstakingly guided the building of the nascent communist movement with not only their theoretical knowledge but also with the practical experiences they had gained all through their lives. They were always open to criticism, as Engels stated once, “labour movement depends on mercilessly criticising existing society...so how can it itself avoid being criticised or try and forbid discussion? Are we then asking that others concede us the right of free speech merely so that we may abolish it again within our own ranks”? Similarly and more importantly, they were never shy to self-critically re-examine their conclusions and if found, wrong, accepted and worked towards arriving at a correct conclusion, as we had seen.

Marx was very clear that once a policy is decided after discussions, it needs to be adhered. The rules written by them for the Communist League stipulate that “subordination to the decisions of the League” was one of the “conditions of membership”. That they insisted on discipline can be seen when they advised a member (Gottschalk) to tender his resignation due to his disagreement with the League’s leadership about its electoral strategy.

Marx, true to his exhortation that it is not enough to interpret, but it is necessary to change the world, not only analysed, but also put in all his efforts to build a party that can transform the society. All the tactics and strategy for Marx are to strengthen these efforts.

It is almost 200 years since the birth of Marx, but his ideas are still relevant. A recent study in Russia conducted by an independent research agency Levada Center, found out that 'more than half of all Russian citizens believe the collapse of the Soviet Union was a bad thing that could have been avoided, while even more people say they would welcome the restoration of the socialist system and the Soviet State'. On the other hand in many countries in the capitalist world, including those advanced capitalist States, there is a growing urge to re-read Marx and learn about the global economic crisis and means and methods to establish a system free of crises. As Marx had taught, capitalism is intrinsically crisis-ridden. The only way to transcend it is to strengthen the party of the working class through building a class alliance based on worker-peasant unity. The road to achieve this is strengthening class struggles and class struggles alone.

For those who accept their 'ideas', as their “existence cannot be denied”, but refuse to practice and try to 'hush up, dilute, attenuate, Marx and Engels have got this to say: “These are the same people who under the pretence of indefatigable activity not only do nothing themselves but also try to prevent anything happening at all except chatter; the same people whose fear of every form of action in 1848 and 1849 obstructed the movement at every step and finally brought about its downfall; the same people who see a reaction and are then quite astonished to find themselves at last in a blind alley where neither resistance nor flight is possible; the same people who want to confine history within their narrow petty-bourgeois horizon and over whose heads history invariably proceeds to the order of the day”.