Komita Dhanda

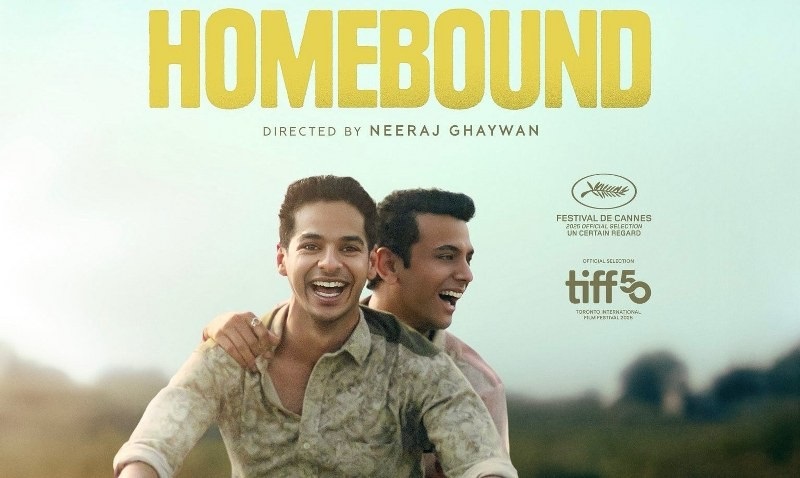

IT’s been five years. The devastating images of migrant workers walking back to their villages to escape the COVID-19 crisis have been buried under the apathetic rhetoric of “Viksit Bharat.” The haunting images of homebound workers struggling to find food, transportation, shelter, medicine, oxygen cylinders, hospital beds, and even the dignity of a proper burial or cremation have slowly disappeared amid the ever-changing content in mainstream broadcast and social media. Recently released in cinemas, director Neeraj Ghaywan’s Homebound (India’s official entry to the Oscars) serves as a painful reminder of the harrowing experiences of the Indian working-class and the systemic neglect they endured, even as the rest of the country witnessed their mass exodus unfold on phone and TV screens.

Adapting journalist Basharat Peer’s New York Times news story about two childhood friends – Mohd Saiyub Siddiqui and Amrit Kumar (real names) from a village in Uttar Pradesh, Homebound constructs its narrative through the lens of caste and religion. The image of Saiyub holding parched and dying Amrit on a highway, hundreds of miles away from their village, moved Peer to follow up on the image and chronicle their story.

The film intricately depicts the innocent, unwavering friendship between Chandan Kumar, a Dalit, and Mohamad Shoaib, a Muslim (with their names changed in the film), both in their twenties and aspiring to join the state police force, as they navigate a world marked by the repeated brutality of systemic social and economic violence. Ghaywan, acutely conscious and unapologetically vocal about his own identity as a Dalit filmmaker, crafts a cinematic language that charts an emotional journey, while unraveling the complex, interwoven lives of Shoaib and Chandan and those around them. Chandan (Vishal Jethwa) and Shoaib (Ishaan Khattar) struggle with questions of identity and the experience of being ‘othered’, as they seek ways to resist, escape, and ultimately reconcile with the socio-political realities that both shape and confine their lives. When asked about his “gotra” and “pura naam”, the embarrassed Chandan replies - Chandan ‘Kumar’ hi hai, sir?” (Chandan Kumar, that’s it). Yet, his hesitant lie about being a “Kaysatha” is enough to set off the government official’s casteist radar, who then makes an indirect insulting remark towards the “category people”, leaving Chandan in an unsettling silence and indignation. Chandan, exasperated, tells Shoaib - Chahe kitne bhi wicket ukhad lein, sarkari faram ke category wale dibbe bhar ki aukat hai hamari? Yehi hi hamari pehchan hai (No matter what we achieve, we will always be reduced to a checkbox in a form. This is my identity). On the other hand, Shoaib’s very name reveals his religious identity, making him a target of casual communal remarks while working as helping staff in a private company.

Ghaywan refuses to reduce his characters to simplistic binaries - Hindu-Muslim, lower caste-upper caste. Instead, he crafts a screenplay that portrays each character with layered complexity and ambiguity. For instance, Mr. Mishra stops Shoaib from filling his water bottle yet invites him to an office party to watch cricket together and subsequently insinuates his (Shoaib’s) allegiance to the Pakistani cricket team. The senior boss, who otherwise trusts Shoaib and is even considering promoting him to the sales team, tries to defuse the situation by dismissing the remarks as just “casual jokes.” In today’s climate, where even cricket is instrumentalised to advance jingoist and right-wing nationalist agendas, the ‘othering’ of Shoaib becomes even more pronounced.

On the other hand, the scenes where Shoaib and Chandan’s families come together to celebrate Eid and enjoy biryani underlines the human connection. In those moments, we are drawn into their world of warmth and togetherness, offering a brief escape from the harsh realities of communal and caste-based hatred. However, these moments are fleeting, moving between moments of precarious hope and its constant dismantling.

Underneath Chandan and Sudha’s seemingly straightforward love story lies a deeply layered deliberation on class and caste, where everyday moments reveal the often unspoken hierarchies and negotiations. The character of Sudha Bharti (Janhvi Kapoor) unsettles the conventional framing of caste and class as reductive binaries as imagined within the academic and political discourse. While both Chandan and Sudha share a caste background, the way they navigate the world is shaped differently by their class realities. Sudha’s experience of caste is filtered through her relative privilege, while Chandan’s remains closely tied to his immediate economic struggle. Coming from a practicing Buddhist family with slightly better economic means than Chandan, Sudha sees education as her path to social mobility and emancipation. “Tabhi log apni kursi humse sata ke baithenge,” (that’s when we will get a seat at the table), she tells Chandan. While Chandan aspires to become a police constable to assert power over those who have humiliated him, Sudha’s ambition to pursue Ph.D. indicates a different kind of dignity - one rooted in intellectual power and respect. By subtly underlining these contrasts, the film depicts how caste is inseparably intertwined with class, aspiration, and access.

Ghaywan deepens the intersection between caste and class by bringing gender into the equation at various moments. Chandan’s sister Vaishali questions the agency that he possesses as the boy in the household that allows him to determine his own future. Her disappointment and frustration at having to abandon her education to financially support the family underscores the precarious position of poor Dalit women, who remain located at the very margins of both caste and patriarchal hierarchies. Together, these characters and cinematic moments reveal the deeply intersectional nature of the structural battles at play underlining the struggles that cannot be fought in isolation but must be confronted simultaneously.

In terms of cinematic form, Homebound deliberately avoids the use of spectacular or overtly dramatic camera angles. The camera remains steady, like a silent observer with an unobtrusive gaze, allowing the narrative and performances to take over. Nonetheless, certain images linger long after the credits roll, urging a reflection that is as necessary as it is uncomfortable.

Phool’s (Chandan’s mother) cracked heels serve as the film’s most striking visual metaphor. The imagery of the cracked heels recurs three times in the film. It first appears during the initial exchange between Phool and Chandan; then surfaces with an elderly village woman - who silently offers water to the parched Shoaib and Chandan, and walks away in silence, the camera following her cracked heels; and finally, when Shoaib gives Phool a new pair of slippers that Chandan had bought for her. In his delirious state, Chandan keeps talking about his mother’s cracked heels, an image that reflects not only his own struggles but also the silent pain carried by his family. The cracked heels as a motif weaves a narrative of intergenerational suffering of his grandmother and mother, a cycle of poverty, and persistent deprivation of means for self-care.

The drone shots of workers moving through vast landscapes, combined with documentary-style footage of migration during India’s COVID-19 lockdown, is a cinematic commentary that evokes collective memories of that tumultuous period marked by uncertainty and fear.

Homebound offers a rare glimpse into a real textile mill, capturing the labour and the cloth making process often unseen in mainstream Hindi cinema. Several migrant workers living in cramped rooms, sharing space and food in between factory shifts quietly build a sense of class solidarity and mutual dependence. However, in moments of crisis, solidarity gives way to self-preservation and exposes the fragility of human connections. When the pandemic hits, this network of mutual support collapses, compelling most to fend for themselves on their journey home, except for Chandan and Shoaib, who choose to stay together as they navigate their way back to their village.

Overall, the film’s strength lies in the fact that the narrative does not merely depict social and economic identities - it interrogates and destabilises them, exposing the silent, often invisible factors that shape human connections across caste, class, religion, and gender. In doing so, Homebound refuses resolution, offering instead a nuanced perspective that is unflinching, and disquieting. It is gut wrenching; our eyes well up, yet the film doesn’t allow us to feel better or worse, but forces us to ‘see better’. This, in a strangely tangential way, reminded me of Brecht whose theatre sought to provoke unsettling clarity rather than provide solace. As long as storytellers and socially conscious artists keep exposing the often invisible violence in the daily lives of the marginalised, there is more than empty hope. Homebound through its emotional yet political tropes gives us a radical hope — a hope rooted in critical thinking and resistance.