Vijay Prashad

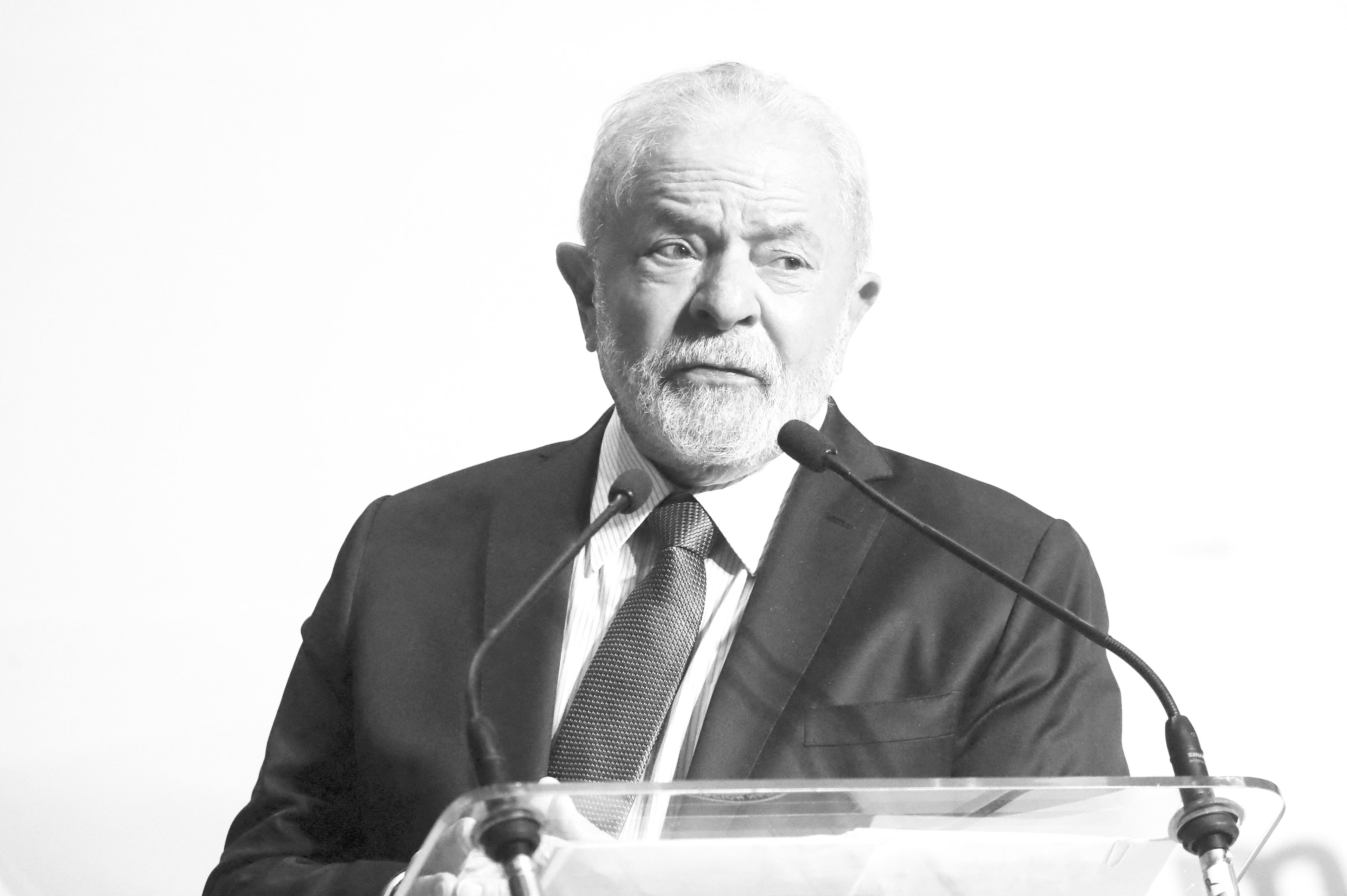

LUÍZ Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula) runs about the stage. He is a man with a great deal of energy. He is telling the story of his time in Iran, when he tried to mediate the conflict imposed on that country by the United States over its nuclear energy policy. Lula, and his foreign affairs minister Celso Amorim, had managed to secure a deal in 2010 that would have prevented the ongoing pressure campaign that Washington conducts against Tehran. There was relief in the air. Then, Lula said, ‘Obama pissed outside the pot’. Barack Obama, the US president, did not accept the deal and crushed the hard work of the Brazilian leadership in bringing all sides to an agreement. Lula tells this story during his presidential campaign against Brazil’s incumbent – and deeply unpopular – President Jair Bolsonaro. Lula’s story puts two important points on the table: he was able to build on Brazil’s role in Latin America to offer leadership in far-off Iran, and he is not afraid of being clear about his antipathy to the way the United States is scuttling the possibility of peace and progress for its own narrow interests. This is the Lula that is now in the lead for the first round of Brazil’s presidential election to be held on October 2.

Fernando Haddad, who ran against Bolsonaro in 2018 and received 45 per cent of the vote but did not win, told me that this election remains ‘risky’. The polls might show that Lula is in the lead, but Bolsonaro is known to play any number of mischievous games to secure his victory. The far-right in Brazil, like the far-right in many countries, is fierce in the way it contests for state power. Bolsonaro, Haddad said, is willing to lie openly, saying offensive things to the far-right media and then when challenged about it by the mainstream media feigning ignorance. ‘Fake news’, Bolsonaro says each time he is attacked. The Left is far more sincere in its political discourse: unwilling to lie, eager to bring to the centre of political debate the issues of hunger and unemployment, social despair and social advancement. But there is less drama in these issues, less noise about them in a media landscape that thrives on the theatrics of Bolsonaro and his followers. The old, traditional right is as outflanked as the far-right of Bolsonaro, who now commands the space once held by men in dark suits who made decisions over cigars and cachaca.

Both Bolsonaro and Lula face an electorate that either loves them or hates them. There is little room for ambiguity in this race. Bolsonaro represents not only the far right, whose opinions he openly champions, but he also represents large sections of the middle class, whose aspirations for wealth remain largely intact despite the reality that their economic situation has deteriorated over the past decade. The contrast between the behaviour of Bolsonaro and Lula during the campaign has been stark: Bolsonaro has been boorish and vulgar, while Lula is refined and presidential. If the election goes to Lula, it is likely that he will get more votes from those who hate Bolsonaro than from those who love him.

Former president Dilma Rousseff is reflective about the way forward. She tells me over a long conversation that Lula will likely prevail in the election because the country is fed-up with Bolsonaro. His horrible management of the Covid-19 pandemic and the deterioration of the economic situation in the country marks Bolsonaro as an inefficient manager of the Brazilian state. However, she points out, in recent days, about a month before the election, Bolsonaro’s government – and the regional governments – have offered policies that have started to lighten the burden on the middle class, policies such as the lifting of taxation on gasoline. These policies could sway some people to vote for Bolsonaro, but even that is not likely. The political situation in Brazil remains fragile for the Left, with the main blocs of the Right (of agro-business, religion, and the military) willing to use any means to maintain their hold on power; it was this coalition that conducted a ‘legislative coup’ against Dilma in 2016 and used ‘lawfare’ against Lula in 2018 to prevent him from running against Bolsonaro. These phrases (legislative coup and lawfare) are now part of the vocabulary of the Brazilian Left, which understands clearly that the bloc of the Right (what is called Centrão) will not surrender their interests if they feel threatened.

João Paulo Rodrigues, a leader of the Movement of Rural Landless Workers (MST) is a close advisor to the Lula campaign. He tells me that in 2002 Lula won against the incumbent Fernando Henrique Cardoso because of an immense hatred of the neoliberal policies he had championed. The Left was fragmented and demoralised at that time. Lula’s time in office helped the Left mobilise and organise, although even during this period the focus of popular attention was more Lula himself than the structures of the Left. During his incarceration on charges that the Left say are fraudulent, Lula became a figure to unify the Left: Lula Livre, Free Lula, was the unifying slogan, and the letter L became the symbol (a symbol that continues to be used in the election campaign). While there are other candidates from Brazil’s Left in the race, there is no question for João Paulo that Lula is the Left’s standard-bearer and is the only hope for Brazil to oust the highly divisive and dangerous leadership of President Bolsonaro. One of the mechanisms to build the unity of popular forces around Lula’s campaign has been the creation of the Popular Committees (comités populares), which have been working to both unify the Left and to create an agenda for the Lula government (which will include agrarian reform and a more robust policy for the indigenous and Afro-Brazilian communities).

The international conditions for a third Lula presidency are fortuitous, Dilma tells me. A range of centre-left governments have come to office in Latin America (including in Chile and Colombia). While these are not themselves socialist governments, they are nonetheless committed to building the sovereignty of their countries and to creating a dignified life for their citizenry. Brazil, the second largest country in the Americas (after the United States of America), can play a leadership role in this new wave of Left governments in the hemisphere, Dilma says. Haddad tells me that Brazil should lead a new regional project, which will include the creation of a regional currency (the sur) not only to be used for cross-border trade but also to hold reserves. He is running to be the governor in São Paulo state, whose main city is the financial capital of the country. Such a regional project, Haddad believes, will settle conflicts in the hemisphere and build new trade linkages that need not rely on long supply chains that have been destabilised by the pandemic. ‘If God wills’, Lula said recently, ‘we will create a common currency for Latin America because we should not be dependent on the dollar’.

Dilma is eager for Brazil to return to the world stage through the BRICS bloc, to offer the kind of Left leadership that Lula and she had given that platform a decade ago. The world, she says, needs such a platform to offer leadership that does not rely upon threats, sanctions, and war. Lula’s anecdote about the Iran deal is a telling one, since it shows that a country like Brazil under the leadership of the Left is more willing to settle conflicts than to exacerbate them, as the United States did. There is hope, Dilma notes, for a Lula presidency to offer robust leadership for a world that crumbles before myriad challenges such as the climate catastrophe, warfare, and social toxicity.