Barry Eidlin

PROFESSIONAL athletes have an enormous amount of power that they put to good use this past week in a series of unprecedented strikes. But workers of all types have similar kinds of power – and could, just like athletes, use it to shut society down to fight injustice.

On August 26, professional athletes in five sports leagues (men’s and women’s basketball, soccer, baseball, and hockey) did something unprecedented: they shut down their workplaces over political issues, namely racial justice and police brutality. These actions have been widely misreported as a “boycott,” but it is important to recognize them for what they are: a strike.

While the scope of the strike and the political nature of the strikers’ demands are unprecedented in professional sports, their actions do follow some established patterns in the history of worker protest. Examining these patterns can offer clues about what these strikes among a small, high-profile group of workers might mean for workers more broadly.

STRUCTURAL POWER

Professional athletes are highly-skilled workers with what sociologist Howard Kimeldorf calls high “replacement costs.” Simply put, they’re not interchangeable parts that can be swapped in and out on a whim, at management’s discretion.

This is obvious for the star players like LeBron James and Giannis Antetokounmpo, but holds for the other players too, especially when you factor in intangibles like team cohesion. This gives players a great deal of bargaining power vis-à-vis management, since it is unlikely that management can respond to their demands by simply firing and replacing them.

It also means that their withdrawal of their highly-skilled labour can start hitting management in the pocketbook almost immediately, and bring business as usual to a grinding halt.

Historically, other far less famous but still very skilled workers with high replacement costs have served as the backbone of labour upsurge. They used the structural power derived from what some might see as their more “privileged” position to build working-class solidarity across different groups of workers and extract concessions from management. So skilled trades people in the plants helped organise the assembly line workers in auto and meatpacking, over-the-road drivers helped organize the “inside” warehouse workers in trucking, and so on.

In this case, the structurally powerful players have leveraged that power in solidarity with marginalized communities of color in which many of the players grew up. A logical next step in line with previous labor upsurges would be for the players to mobilize in solidarity with the tens of thousands of service workers who keep their teams functioning and the stadiums where they play up and running.

WORKPLACE-BASED POWER

The players exerted their power where it is strongest: in the workplace.

Like previous generations of strikers, they downed their tools and refused to work. Their actions are reminiscent of the “quickie” wildcat strikes that were far more common in times when labour was stronger.

Then, as now, such strikes served as a kind of “instant grievance procedure,” where instead of waiting for issues to be resolved through a long, drawn-out bureaucratic process, workers forced management’s hand by halting production.

This culture of “quickie strikes” persisted in several industries throughout the post-World War II decades, even as unions as a whole bureaucratized. But it has largely disappeared in recent decades, as employers have waged a relentless offensive to assert their uncontested “right to manage” via management techniques, technological change, and legal rulings that have hemmed in workers’ ability to fight back.

Indeed, the players’ actions themselves were technically illegal according to their contracts. But their rapid spread and (tentative) resolution only gave proof to the old labor adage that “there is no such thing as an illegal strike, only an unsuccessful one.”

Strikes have been on the rise in recent years after decades of quiescence, sparked by the “red state revolt” of teachers in 2018. As more workers strike and win, it becomes a more feasible option for other groups of workers. While most workers will never become professional athletes, they may seek to follow the athletes’ example of exerting collective power.

ASSOCIATIONAL POWER

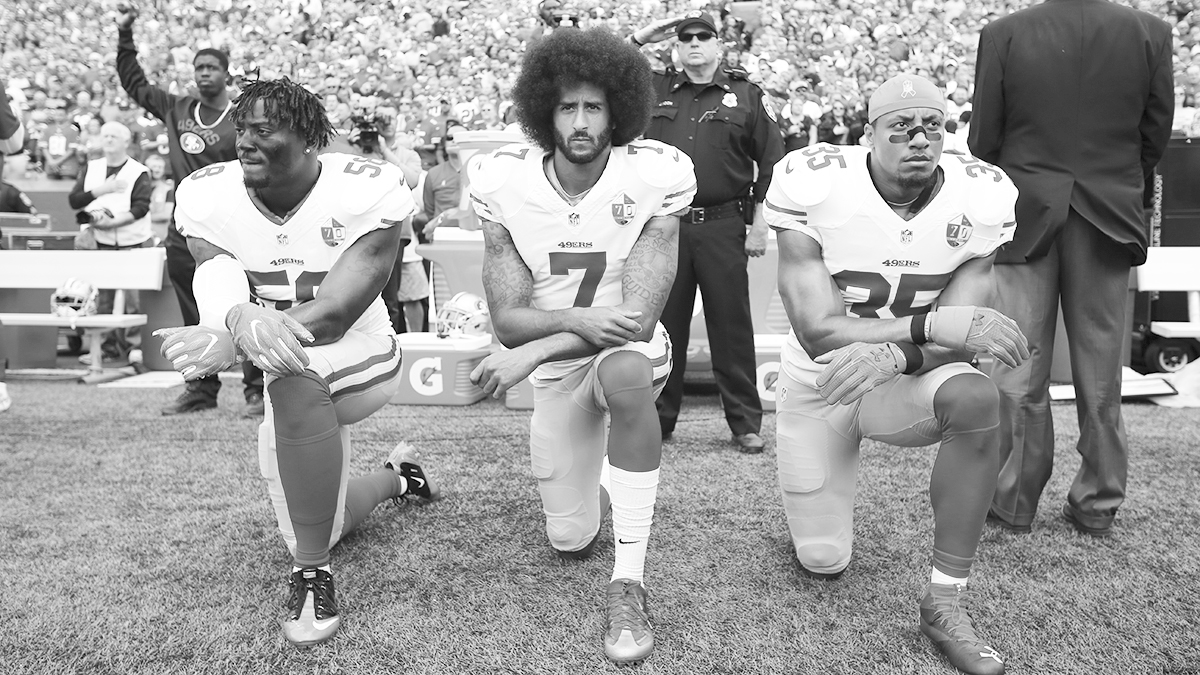

Even with high replacement costs and structural power, the athletes’ protest could not have had the effect it did without associational power. Prominent athletes like Colin Kaepernick, Megan Rapinoe, and others have taken principled political stands in the recent past, but without the same effect. And in Kaepernick’s case, his political stance cost him his career.

To shut everything down, athletes had to get organised. Some initial efforts started to take shape in the aftermath of Kaepernick’s courageous individual protest, but it appears that the quarantine bubbles in which the players are living created an organizing pressure cooker of sorts. Players were able to talk and strategize with each other, while also feeling frustrated at not being able to exit their bubbles to engage in the movements unfolding outside. Bringing sports to a halt for a day burst the bubble, making athletes’ voices heard around the world.

Many workers today are facing intolerable and unsafe working conditions in the midst of the pandemic, alongside the millions thrown into unemployment. While far from a mass movement at this point, increasing numbers of workers are bucking the odds and getting organised. In demonstrating the power of collective action, the players’ strike could set a broader example.

SYMBOLIC POWER

Pace Charles Barkley, athletes are indeed role models. While they may use that role to set an example as trend-setters, fashion icons, or paragons of individual achievement, there is also a long tradition of athletes using their moral standing to boost calls for social justice. Beyond Kaepernick and Rapinoe, we can think of Caster Semenya’s fight against gender policing, Billie Jean King’s fight for gender equality, Tommie Smith and John Carlos Black Power salute at the Mexico Olympics, Muhammad Ali’s principled stance against the Vietnam War, and many more.

This symbolic power may have limited effects on its own, but when combined with structural and associational power, it can be electrifying. It is unlikely that a similarly structurally-powerful, well-organized group of workers without the players’ public prominence and moral standing would have generated the same response.

Not all workers can mobilize their celebrity and role model status to advance causes for social justice like the players have. But they can and do use moral narratives to shape the terms of debate around their struggles. We saw this with the recent teachers’ strikes, where they forged alliances with parents and students by drawing a parallel between their working conditions and students’ learning conditions. Or with the Fight for $15 minimum wage campaign, which managed to transform that policy from a pipe dream to actual policy within a few years. Going further back in time, we can think of the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott or the sanitation workers who brought Martin Luther King, Jr. to Memphis for his final battle as examples of struggles that combined organizing with a powerful moral narrative.

As momentous an event as the players’ strikes are, so far they are just that: an event. Again looking to history as a guide, such events can serve as a watershed for a larger upsurge, as the 1934 strikes in Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Toledo launched the labour upsurge of the 1930s. At other times, they can fade away.

Given the organising that has gotten players this far, it is unlikely that the player protests will simply dissipate, especially with how successful they have been. The key question is how far the protests will spread.

Courtesy: Jacobin