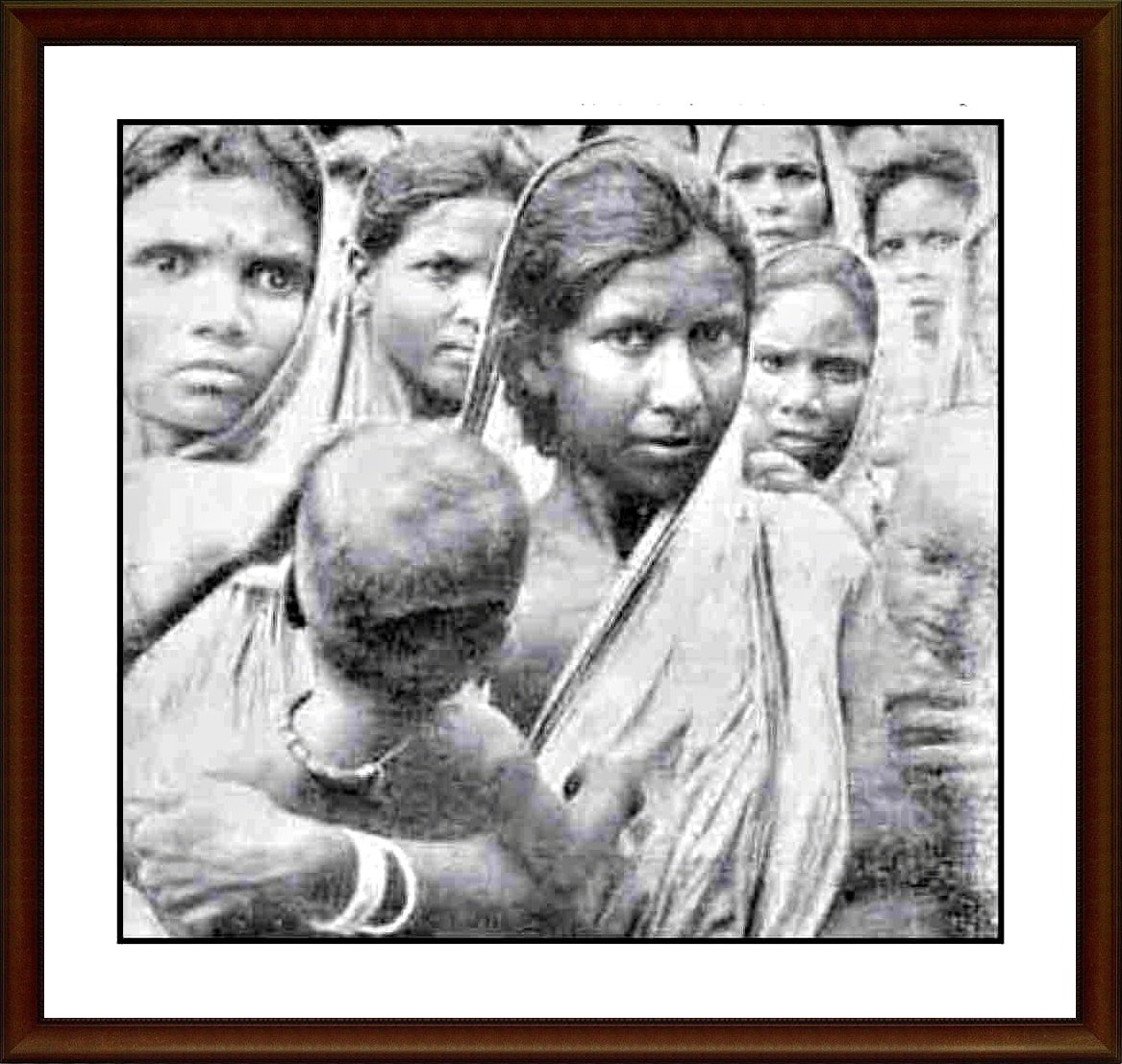

THE struggle for food, waged by the people of West Bengal is an immortal saga, written in the blood and suffering of people roused to action in defence of their right to live. The struggle for food started on July 13, 1959 and continued till September, in which dozens of people died due to the then Congress government’s brutal repression – hundreds more were injured and thousands incarcerated. The struggle assumed the form of a huge upsurge of the entire people of Bengal. Millions were on the move – the struggle was not confined to Calcutta and the district towns, but spread to the remotest villages. Thousands upon thousands of peasants, workers, students, middle-class employees, professionals and other sections were swept into the struggle.

The struggle for food started when under the Congress government led by the first chief minister of West Bengal, Dr B C Roy, the food crisis and near-famine conditions became permanent features of the state’s economy. The food situation in Bengal took a serious turn since 1955, particularly during the months between April and September, when it became more acute. The price-index of rice rose from Rs 382 per ton in December 1955 to Rs 532 in December 1956. The situation worsened in early 1959. Mass starvation, deaths, suicides and tragic migration of hundreds of thousands of people from the rural regions to the cities, particularly Calcutta, in search of food and employment became a regular feature. The rule of the Congress government since the independence of the country, instead of ameliorating the problems of the people had led to a situation where, large number of peasants lost their land and employment and became paupers.

The Communist Party played a glorious role throughout the struggle. The Party took the initiative to mobilise large masses of the people by forming a broad-based platform called the Price Increase and Famine Resistance Committee (PIFRC). Through the PIFRC, it contributed immensely in shaping and implementing the decisions of the committee and never lost grip over the situation, even during severest crisis. The cadre of the Party were always and everywhere with the people – in the thick of lathi charges and firings, in the battle against goondas and agent provocateurs, in the efforts to persuade infuriated people not to allow their hatred and indignation be diverted into undesirable channels.

Leaders of the Communist Party, who were elected to the legislative assembly discussed the points suggested by the PIFRC to ameliorate the food crisis in the state, on the floor of the legislature since the budget session in February. But the government refused to act and instead facilitated the profit generating interests of the traders. As the lean months approached, it had suspended price control order, thus legalising profiteering and black-market prices. It refused to procure adequate quantities of paddy and rice directly from the peasants and also rejected the demand for increasing the levy on the production of rice mills. The no-confidence motion moved by the Communist Party in the assembly exposed the utterly anti-people and pro-hoarder food policy of the government.

The Communist Party placed a comprehensive alternative policy before the government for its consideration through the PIFRC. This alternative policy suggested measures to be adopted for increasing food production in the state, measures for ensuring proper distribution of the grains purchased directly from the peasants and also certain relief measures to be provided to the old, infirm and the unemployed. The Party also suggested the formation of food advisory committees at all levels as was being done at the same time in Kerala by the Communist Party led government. The Party further suggested distribution of surplus land to the landless agricultural labourers and poor peasants, extension of modified rationing scheme to cover all needy people, building up of adequate food stocks, reduction of prices and curbing of hoarding and speculation.

The state Congress government, instead of accepting these demands, adamantly turned down every single suggestion given by the Communist Party and the PIFRC. As the food situation worsened, the Communist Party, through the PIFRC, called upon the people to mobilise. Rallies and demonstrations were held all over the state and within a short time, the movement assumed a statewide character. This was followed by the call for a general strike, which received tremendous response from the working class. All these protests failed to move the obstinate Congress government.

The PIFRC, left with no other alternative, called for direct action. The struggle was first launched in Midnapore district on July 13 and within ten days it spread to all other districts. On August 8, the state food convention was organised, which called for direct action throughout the state from August 20. From that day onwards, the movement gained further momentum and events moved swiftly.

The B C Roy government started acting against the movement, by first arresting over 100 leaders of the Left parties, trade unions, Kisan Sabha and other mass organisations. This was projected as a blitzkreig to cripple the movement, which of course failed in its objective. On August 20, the pre-determined day of direct action, thousands of people mobilised and gave the movement an unprecedented mass character. In Calcutta, more than 30,000 people mobilised and moved forward to demonstrate in front of the house of the food minister. The PIFRC called for organising a giant rally in Calcutta on August 31, a statewide general strike and hartal on September 3. These decisions of the PIFRC and the response it evoked from the people of Bengal, sent the government into a frenzy. It unleashed savage repression throughout the state from August 25. Students joined the protests on September 1 and College Street in Calcutta was a scene of pitched battles. Between August 31 and September 4, more than 80 people were killed in police firing and lathi charges and more than 3000 were wounded. At least 200 people went missing and thousands were arrested.

In order to break the ranks of unity, police raided working class residential areas (bastis) and severely beat the inmates. Not satisfied with this, they teargassed these bastis. Undaunted, the entire working class participated in the successful general strike. Every industrial area witnessed a great working class upsurge. In order to break the ranks of the working class, the government even tried to foment divisions among the working class in the name of Bengali-Bihari identity. All these measures adopted by the government failed to break the unity of the working class with the peasantry and this was a significant aspect in this movement.

A study of the arrested people shows that over 75 per cent of them were peasants, while the rest were workers, students and middle-class employees. Thousands of women were part of all these sections who courted arrest.

Police brutalities, personally directed by the chief minister B C Roy, reached never before seen proportions. In many instances, the police sealed all the routes of retreat, threw a massive cordon round the demonstrating people and brutally beat them. From the injuries received by the people, it became clear that the police shot to kill and cause grievous injuries to the protesters. Even those who were arrested were subjected to inhuman torture in the police lock-ups. And most gruesomely, in order to hide the evidence of their mass slaughter, the police burnt scores of dead bodies of martyrs in the middle of the night. Whole areas of Calcutta and Howrah were scenes of such savage ‘mopping-up’ operations.

The Communist Party played a heroic role all through these protests. Particularly noteworthy was the role played by the Party daily Swadhinata. The comrades working in the paper and printing press transformed the paper into a real people’s organ and an extremely powerful weapon of the struggle. Braving serious risks, they collected shocking reports and photos of police brutalities and printed them in the paper, rousing people into action.

The Central Committee of the Communist Party appreciated the struggle of the people of Bengal and called for solidarity campaigns throughout the country. The actions of the Congress government drew condemnation from people all over the country. The class character of the Congress was further exposed as it was during this period that it had dismissed the Communist government in Kerala on the pretext of ‘safeguarding democracy’. On other hand, in Bengal, it was this very Congress government, which was violating democratic principles with utter impunity by trampling upon people’s rights.

Along with the hypocrisy of Congress which stood exposed, the contrast between it and the Communist Party could never be more glaring. The 1959 food movement also had an impact on the internal debates within the CPI, particularly about the attitude towards the Congress party.

The PIFRC formally announced the withdrawal of the food movement on September 26, 1959, on the day in which the foundation of a permanent Martyrs’ Column was laid. An unforgettable silent rally was brought out in Calcutta which demanded a public inquiry into the police atrocities, proper compensation for the martyrs and the immediate resignation of the state food minister.

The spirit of the food movement and its echoes continue to be heard.