THE Meerut Conspiracy Case (1929) is a landmark in the history of India’s national liberation struggle. It came at a time when the entire capitalist world was reeling under the Great Depression, whereas, the newly born socialist State of Soviet Russia was making tremendous advances. During this period, militant working class struggles, majority of which were led by communists and revolutionaries, reached a new high.

The number of worker strikes, which had reached a height in 1921 (during the period of the Khilafat-non-cooperation movement), decreased with the withdrawal of non-cooperation movement. But from the second half of the 1920s, once again we witness an increase in the number of man-days lost due to strikes. This is reflected in 1928-29, where there were 203 strikes and the man-days lost were 3,16,47,404.

The Great Depression which set in from late 1929 affected India in several ways and the impact fell hard on working class and peasantry, forcing them to come out in even larger numbers in protests. This phenomenon continued into the early years of the 1930s. The intensification of workers struggles was a demonstration of the political consciousness that had begun to grow along with the working class movement.

A majority of the working class and peasant struggles were led by the communists under the banner of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Parties (WPP). In 1928, the Bardoli agitation, one of the most successful peasant mobilisations took place at the same time as the Girni Kamgar strike in Bombay. Though the two were quite unrelated and did not have any organisational link, the British feared a link-up between the two and were ‘certain that the communists would use the Bardoli situation, if the government took action there’. Such was the fear of communists among the British.

The activities of the communists and the WPP had contributed to the growth in consciousness of the common people, who could now locate the struggle for independence as a part of the world-wide anti-imperialist struggle. The Congress too was forced to accept this fact. Another major impact that the work of the WPP’s had during this period was on revolutionary nationalists. Many of them came under the influence of communist ideas and the first indication of a substantial change in the general outlook of this section was the growth of communist movement. A clear evidence of such change was the formation of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association under the leadership of Bhagat Singh. In those days when people in general were thinking in terms of either ‘bomb-politics’ or Gandhian non-violence, the propaganda carried out by the WPP and the Communist Party brought ‘working class politics’ to the fore. Youth were attracted to the idea of direct action, rallying the entire working masses for full independence, as propagated by the communists.

The British precisely feared this kind of spread of communist influence among the masses and immediately initiated measures to curb communist activities. In December, 1928, the British Secretary of State revealed to the Viceroy that the government was gathering information in connection with the ‘proposed conspiracy trial’. Viceroy Irwin wrote to the Governor of Bengal (January 18, 1929): “We have….at present reasonably good hopes of being able to run a comprehensive conspiracy case against these men. If we could do this, it would in our opinion, deal a more severe blow to the Indian Communist movement than anything”.

Thus initiated, the Meerut Conspiracy Case began on March 15, 1929, when the District Magistrate of Meerut issued arrest warrants against the accused persons. The Governor General of India, Lord Irwin, had granted sanction to launch prosecution under Section 121-A of the Indian Penal Code just the day before.

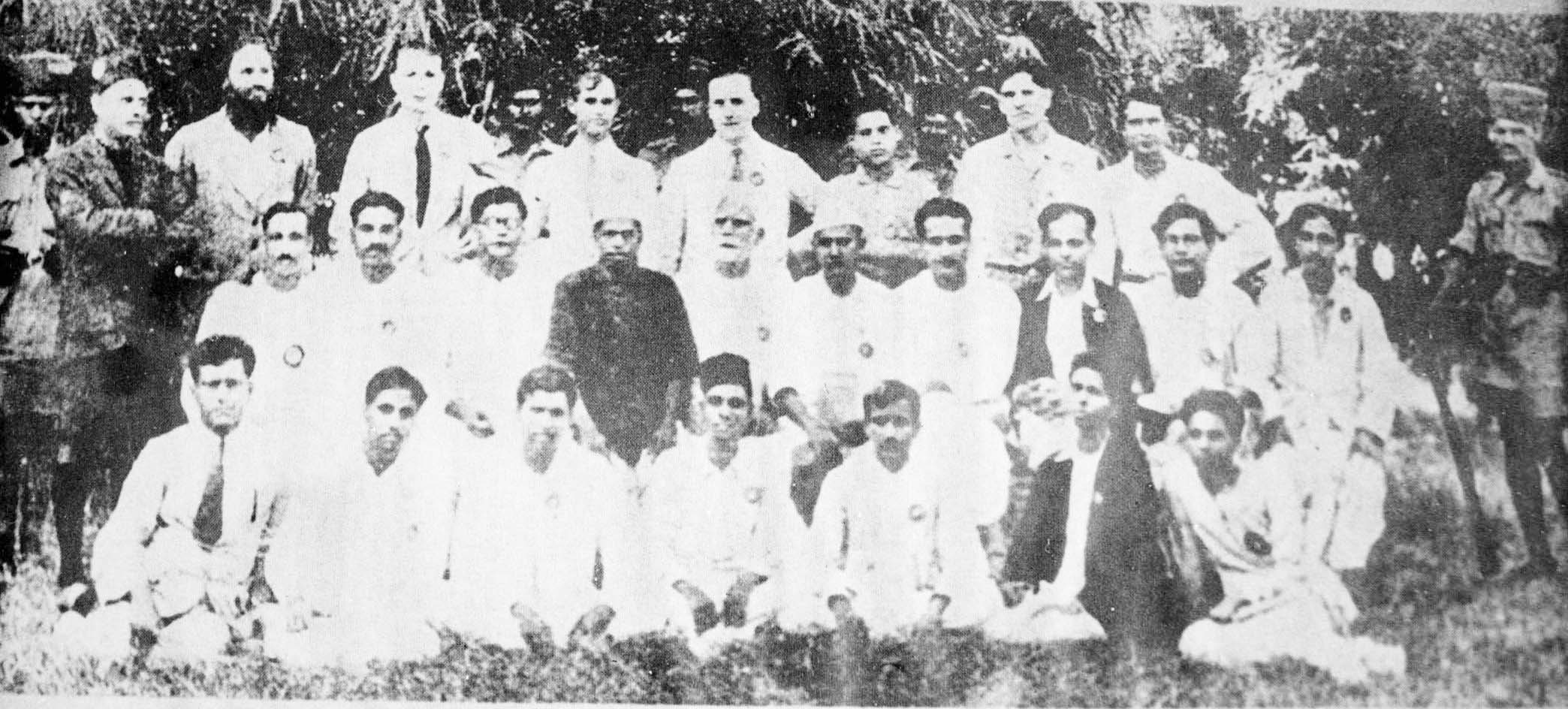

On March 20, 1929, thirty-one communist/labour leaders were arrested in different parts of India. Most of them were well-known figures in the trade union and working class movement. Of them, thirteen were from Bombay, ten from Bengal, five from UP, three from Punjab and three were Englishmen. The arrested included eight members of All India Congress Committee and almost every member of the executive committee of the recently established WPP. Their arrest was accompanied by thorough raids and house searches.

Selection of Meerut as the place for trial was well-planned. Primarily, the authorities wanted to avoid trial by jury. Both in Bombay and Calcutta, two principal centres of communist activities, the case would have been tried by the High Court with a jury. A ‘very secret’ document of the Home Department exposed the real motive of the British: “We could not….take the chance of submitting the case to a jury. However good the case, there could be no assurance that a jury would convict, and we cannot put the case into Court unless we are convinced that it will result in conviction”. The same document further states: “With the present dangerous atmosphere prevailing among the labouring population, both in Bombay and Calcutta, it is clearly undesirable to have the trial in either of these places”.

The case was conducted on a ‘gigantic scale’, to quote the final judgement of the Allahabad High Court. The proceedings lasted for nearly four-and-a-half years. The evidence in the case consisted of twenty-five printed volumes of folio size. There were altogether, 3,500 prosecution exhibits, over 1,500 defence exhibits and no less than 320 witnesses were examined. The judgement was in two printed volumes covering 676 pages of folio size. The government spent sixteen lakh rupees from the public exchequer on the case even before it was referred to the High Court.

Unlike in previous ‘communist conspiracy’ cases, the prisoners at Meerut decided to use the court as a platform to propagate their agenda to the greatest extent possible. Muzaffar Ahmad told Adhikari that they should turn the Sessions Court into a propaganda platform by making political statements, for which they decided to equip themselves through study. The general statement on behalf of all the accused was formally introduced by RS Nimbkar.

The Additional Sessions Judge, in his judgement stated that the ‘main achievements’ of the accused were the ‘establishment of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Parties’ and “of deeper gravity was the hold that the members of the Bombay Party acquired over the workers in the textile industry in Bombay as shown by the extent of the control which they exercised during the strike of 1928 and the success they were achieving in pushing forward a thoroughly revolutionary policy in the Girni Kamgar Union after the strike came to an end”.

In all twenty-seven of the accused were convicted. They were: Muzaffar Ahmad – transportation for life; transportation for a period of twenty years – SA Dange, Philip Spratt, SV Ghate, KN Joglekar, RS Nimbkar; transportation for a period of ten years - BF Bradley, SS Mirajkar, Shaukat Usmani; transportation for a period of seven years – Mir Abdul Majid, Sohan Singh Josh, Dharanikanta Goswami; transportation for a period of five years – Ayodhya Prasad, Gangadhar Adhikari, PC Joshi, MG Desai; four years rigorous imprisonment – Gopen Chakraborty, Gopal Chandra Basak, Hutchinson, Radharaman Mitra, SH Jhabwala, KN Sehgal; three years rigorous imprisonment – Shamsul Huda, Arjun Atmaram Alve, GR Kasle, Gauri Shankar and LR Kadam.

Following the verdict, all 27 convicts appealed to the Allahabad High Court, which delivered its judgement in August, 1933. The High Court dismissed all the charges framed against nine and for the others, reduced the punishment to rigorous imprisonment. The period of remission already earned by them was taken into account and all of them were released in November 1933.

The entire trial received wide publicity and evoked solidarity of the working class all over the world. The Meerut trial was perhaps unique for the strong solidarity initiative in the form of an organised movement in India and abroad, particularly in Britain. Comintern condemned the arrests and British workers and communists built a determined solidarity movement. They collected funds for the prisoners. The radical British press also highlighted the issue and sympathised with the prisoners throughout the years of the trial. From 1929 to the end of 1933, the solidarity movement for Meerut prisoners became a militant political movement, which helped build up a favourable public opinion in support of India’s struggle for freedom.

Bhagat Singh and his comrades, themselves under trial (Lahore Conspiracy Case), expressed their solidarity with the Meerut prisoners. Leader of the self-respect movement in the Madras province, Periyar EV Ramaswamy, openly sympathised with the Meerut prisoners. Many Congress leaders, including Gandhi denounced the British and expressed their sympathies with the Meerut detainees.

Workers, especially in Calcutta, Bombay and other working class strongholds suspended work, protesting the detention of their leaders. AITUC openly denounced the trial. Students and youth too joined the protests in many cities.

The Meerut solidarity movement showed the potential might of the working class. In India, the trial provided communists an ideal platform to come to a common understanding about strategies and tactics and to propagate them through broader channels. Following the release of the communist prisoners in late 1933, the Party was able to find a stronger political and organisational foundation to spread its activities. It was also successful in expanding its support base among the revolutionary nationalists who were in search of an alternative path for national liberation.

The facts and arguments from Meerut Conspiracy Case and Lahore Conspiracy Case, which were going on simultaneously, helped millions of youth in the country to choose the path of mass revolutionary struggles.