THE most important lesson that people learned from the Great October Socialist Revolution was the power of mass actions and the results they can achieve. They were inspired by the thought that if the people of Russia can defeat Czar and usher in a peoples’ State, the same weapon can be used by the people of India to achieve freedom from British colonial rule. The growing discontent against British rule, the withdrawal of non-cooperation movement and the limitations of various revolutionary groups that were existing in India during that period, made people look for alternatives and it is in this scenario that the ideas of the October Socialist Revolution caught their imagination.

The British were alarmed at the spread of communist ideas in India and the news of the formation of Communist Party had further heightened their fears. They reacted by arresting the communist revolutionaries entering India from the Soviet Union and locked them up in the Peshawar jail. These revolutionaries were charged with sedition. In 1923, sentences were passed on them – most of them were sentenced to rigorous imprisonment ranging from one to ten years. Among those sentenced was Mohd Shafi, who was elected as secretary of the CPI in Tashkent. The Peshawar Conspiracy cases, there were five in all, were in reality the first communist conspiracy case in India.

The Home Department sent a warning to all government officials and urged them to act immediately to curb the threat of communism: “Wherever communism manifests itself, it should be met and stamped out like the plague. The spread of communism in India is not one of those problems which may be looked at from a particular ‘angle of vision’; it must be looked straight in the face and it must be fought with the most unrelenting opposition”.

In spite of all their efforts, the British failed to stop the spread of communist ideas across the country. Many groups started functioning independently, spreading the ideas of socialism in cities and industrial centres. Shaukat Usmani, who had returned from Moscow initiated a group in Benaras, Muzaffar Ahmed in Calcutta, Dange in Bombay, Singaravelu Chettiar in Madras and Ghulam Hussain in Lahore.

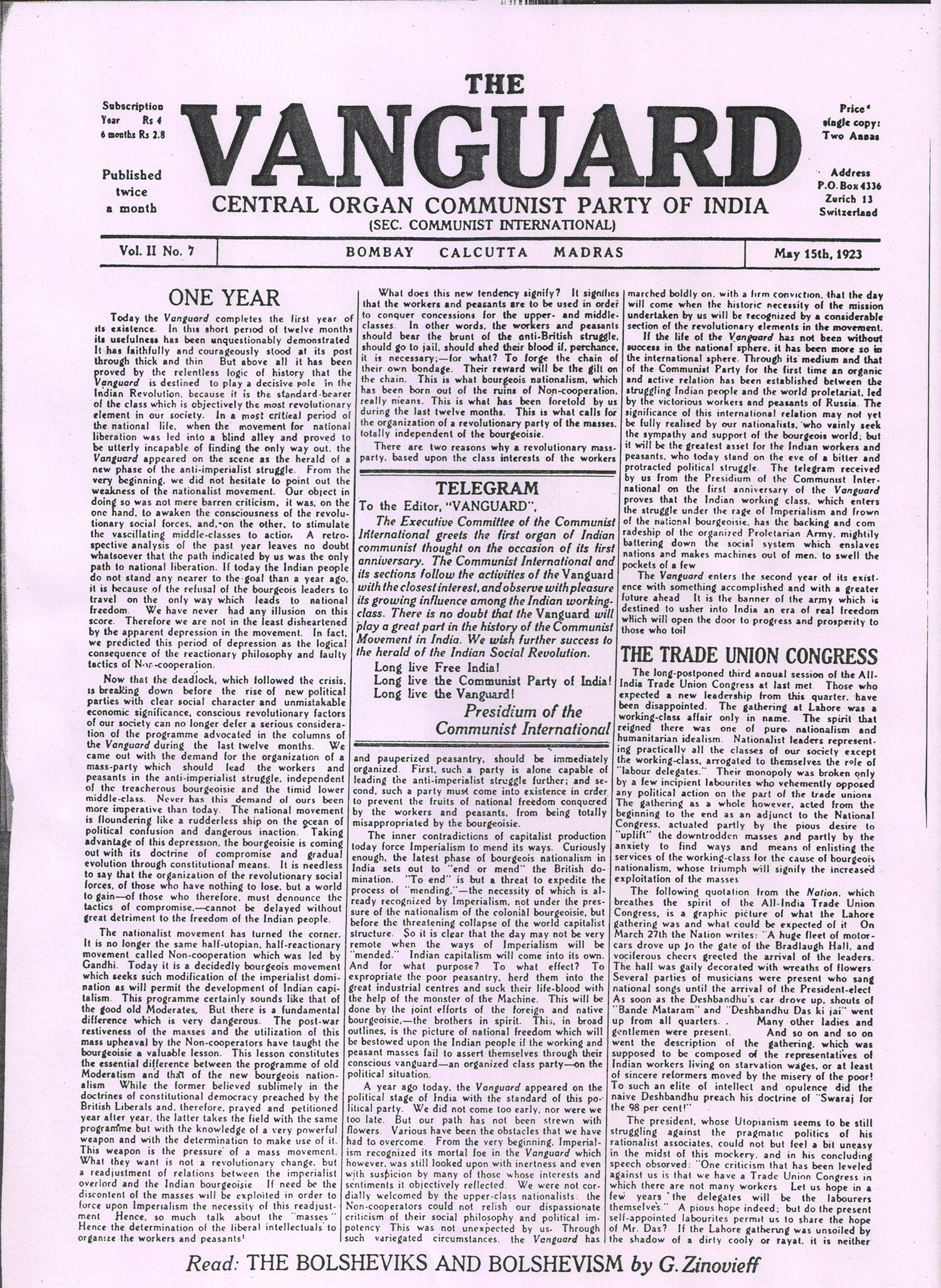

Though the British had banned the journal Vanguard, brought out by MN Roy, it was clandestinely shipped into the country and reached its readers. Apart from the articles that appeared in this journal, the knowledge acquired through reading various books and news reports on Soviet Union and socialism, helped the pioneers of the communist movement to further popularise these ideas.

Muzaffar Ahmed, along with the famous Bengali poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam ran the evening daily, Navyug (New Age). The uniqueness of this paper was that it contained many news items and reports about the conditions of workers and peasants. It is in the course of bringing out this paper and writing editorials that Muzaffar Ahmed got attracted to the Third International. Abdur Razzak Khan, Abdul Halim had joined them and this group played a prominent role in spreading communist ideas in Calcutta.

Shripad Amrit Dange was expelled from college for his participation in student movement and had participated in the non-cooperation movement. He was unable to accept Gandhi’s ideas and had written a book Gandhi vs Lenin in 1921. He started bringing out an English weekly called Socialist, a first in the history of our country that a journal was brought out in that name. Dange worked amongst the workers in Bombay and started organising them.

Similarly, Ghulam Hussain, who was working as lecturer in a government college in Peshawar, met some of the revolutionaries who had returned from Moscow and after discussions with them, gave over his job and started organising people in Lahore. He brought the Urdu monthly called ‘Inquilab’, along with Shamsuddin Hassan and also became the secretary of the North-Western Railway Workers’ Union. They made the Lahore National College as the centre of their activities. In rest of the Punjab, many of the comrades who were connected with the Ghadar movement also formed such groups. Shaukat Usmani, who had returned from Moscow, settled in Benaras and started work among the students. He was also active in Kanpur and surrounding areas.

In Madras, Singaravelu Chettiar, a lawyer turned activist was involved in organising workers and peasants. He published Labour Kisan Gazette, a fortnightly in English and Thozhilalan a weekly in Tamil. Singaravelu in his ‘Open Letter to Mahatma Gandhi’ (1921), wrote: “I believe that only communism, that is to say holding land and vital industries in common for the common use and benefit of all the workers in the country, will bring a real measure of contentment and independence to our people….When we can use non-violent non-cooperation against political autocracy, I fail to see why we should not use the same against capitalistic autocracy? We cannot fight against the one without fighting against the other”. He clearly stated that along with political independence, workers also need economic independence and urged for the formation of an organisation for workers and peasants. This organisation, according to him, should adopt the ‘rules and regulations of the International Working Men’s Association of Moscow’ (Communist International), with ‘suitable modifications made to suit Indian conditions’. In 1923, Singaravelu started the Labour Kisan Party, by celebrating May Day for the first time in Madras.

The British Home Department had identified that ‘by the autumn of 1922’, the following ‘communist publications’ were in existence: “Atma Sakti, Dhumketu, Desher Bani, Navyug (in Bengal), Socialist (Bombay), Labour Gazette, Navayugam (Madras) and Inquilab, Kirti (Punjab)”. Apart from these publications, they had also noted many of the mainstream Indian media to be under the ‘influence of communism’. They specifically mentioned Amrita Bazar Patrika (Calcutta), Servant (Bombay) and Bande Mataram (Lahore) in their reports.

The leaders of all these various groups in the country were in correspondence with each other, though they could not directly meet due to various factors. Apart from the commonality in their thoughts, MN Roy also played an important role to coordinate their activities.

In the Gaya session of the Indian National Congress (1922), Singaravelu met with Dange and addressed the gathering. MN Roy described this as an historic event, where a ‘grey-bearded man (of over sixty)’ openly proclaimed “himself a communist when younger spirits quailed in terror at the prospect of government prosecution and ostracism from the ranks of ‘respectable nationalism’.

The slow but steady spread of the communist movement caused serious anxiety to the British. The Home Department noted that “its (communist party’s) menace to India’s peace and prosperity had become sufficiently serious to necessitate the first important communist conspiracy case”. In May 1923, Shaukat Usmani was arrested in Kanpur and Muzaffar Ahmad was arrested in Calcutta. A few days later Ghulam Hussain was arrested in Lahore. All three of them were detained in various jails without trial under Regulation III of 1818. In December 1923, Nalini Gupta was also arrested and imprisoned under the same Regulation. He was not a member of any party, but proclaimed himself a nationalist revolutionary.

In March 1924, a charge sheet was filed in the court of the District Magistrate, Kanpur, under section 121-A of the Indian Penal Code against (i) SA Dange; (ii) Shaukat Usmani; (iii) Muzaffar Ahmad; (iv) Nalini Gupta; (v) Ghulam Hussain; (vi) Singaravelu Chettiar; (vii) Ramcharan Lal Sharma and (viii) Manabendra Nath Roy (MN Roy). Only the first four of them were produced before the Court. Singaravelu Chettiar was confined to bed with illness, hence was not brought to the Court and was released on bail. Ghulam Hussain bought his freedom by confessing before the police and begging for mercy. Ramcharan Lal Sharma could not be arrested as he had sought the protection of the French government in Pondicherry. MN Roy was in Europe, so he too was not arrested. Proceedings were thus launched only against Muzaffar Ahmad, Dange, Shaukat Usmani and Nalini Gupta. The government called this as the ‘Kanpur Bolshevik Conspiracy Case’.

Muzaffar Ahmad wrote in his memoirs that “Whatever might have been the calculations of the British, however much we might have suffered, the Kanpur Bolshevik Conspiracy Case provided inspiration also to our movement. To some extent, it contributed to the considerable accession of strength which took place in our movement up to the year 1928”.

Unlike during the Peshawar Case, many newspapers reported about the Kanpur Case and some of them even supported the communists. Clearly, repression failed to stop the spread of communist influence. The British grudgingly accepted that ‘communism had come to stay’ and quoted a Calcutta newspaper report: “the fear of the law against communism has been removed”.