Prakash Karat

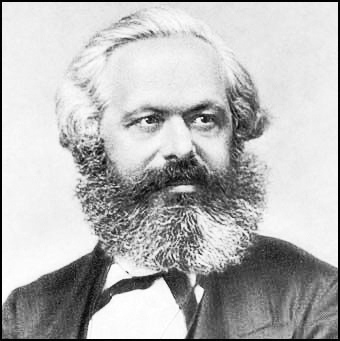

MAY 5, 2019 marks the conclusion of the year-long observance of the 200th birth anniversary of Karl Marx, who was born on May 5, 1818.

The 200th birth anniversary was observed worldwide, including in India. Conferences, seminars, discussions, and a host of publications regarding Marx and Marxism marked the year.

What these diverse activities established was the abiding relevance of Marx and his thought in the contemporary era, that of the 21st century. For us in India, in the midst of an election battle against rightwing Hindutva forces and their authoritarian leader Narendra Modi, the year-long observance brought out one specific aspect of the contemporary relevance of Marxism sharply, that of Marxism as a method with which to understand the meaning of the rightwing offensive under way in India after the assumption of power by the Modi government.

The rightward shift, which is a global phenomenon, is continuing. In 2018, there were eight governments in the European Union that were led by far-right or ultra-nationalist parties – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia. This is apart from the existence and rise of far-right and xenophobic parties such as the National Front in France, the Alternative for Deutschland in Germany, the Golden Dawn in Greece, Finns Party in Finland, and Party of Freedom in Netherlands.

The counter-offensive of the right has been unfolding in South America with the election of the extreme rightist Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and the siege, backed by the United States, laid upon the Maduro government in Venezuela.

The past year also saw the re-election of Recep Erdogan as President of Turkey. Last month, Benjamin Netanyahu was re-elected Prime Minister in Israel. Narendra Modi belongs to this ilk. The rightwing Shinzo Abe is now serving his fourth term as the Prime Minister of Japan. On top of it all, there is the ultra-right President of United States, Donald Trump, who was elected in November 2016.

All sorts of theories have been bandied about regarding the rise of such leaders and rightwing regimes. Many bourgeois commentators talk about the rise of a “new populism.” Others speak of the rise of “strongmen” in politics. But these are either misleading or imperfect assessments of the phenomenon.

Although the term “populist” can, at most, describe a style of politics, not a political philosophy, liberal commentators use the term to lump leaders of the right and Left together – whether Hugo Chavez, Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, or Jeremy Corbyn. Similarly, “strongmen” can be rightwing authoritarian leaders like Erdogan or Hungary’s Viktor Orban or Left-nationalist leaders such as Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela or Evo Morales of Bolivia.

We have to rely on Marxist theory and method to grasp what is happening.

In his famous The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx had written that human beings “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.”

Marx was writing about the rise of Bonapartism, or, in other words, about the rise of an authoritarian leader in a situation where the ruling class in a capitalist society is no longer able to maintain its rule by constitutional and parliamentary means, or when the crisis is at a stage of a rupture in the existing political order. Such a situation invests a Bonapartist leader or regime with a certain degree of autonomy from the ruling classes. This does not mean that the Bonapartist regime goes against the ruling classes; on the contrary, it acts to protect their interests.

We have to see the rise of the far-right and authoritarian leaders in the context of the vagaries of global finance capital, the restructuring of societies by neo-liberalism and the crisis that has enveloped the neo-liberal system itself. The elected leaders thrown up by the rightward shift are characterized by their fealty to neo-liberal policies, national chauvinism, and exclusionary rhetoric. Some of the elected authoritarian leaders have the Bonapartist-like character of which Marx spoke.

Neo-liberalism has gone about restructuring society in the past four decades. An outcome of this restructuring has been to push the working class to the margins. Neoliberalism has generated a plethora of types of identity politics and competing ethnic and religion-based nationalisms. The same period of four decades saw the retreat of socialism and universal values, thus opening up new ground for the growth of a variety of rightwing ideologies and movements.

The 2007-08 global financial crisis marked the beginning of the still-unfolding crisis of the neo-liberal order. This crisis of neo-liberalism has, as noted by the 22nd Congress of the CPI(M), created new contradictions leading to ruptures and the emergence of new political forces and rising tensions.

With the neo-liberal order reaching a dead-end, the ruling classes are unable to run Constitutional and state institutions smoothly and in the old way. Neo-liberalism has hollowed out democracy and democratic political institutions. It is in such a milieu that ultra-right and often maverick political figures rise. They seek to project themselves as being above the discredited political establishment.

Trump, Erdogan, Netanyahu and Bolsonaro are all products of this process, though the exact political circumstances and the use of reactionary ideologies and divisive nationalisms varies in each case.

Liberal democracy, the favoured form of rule of capital, is also in crisis. To people in the Western countries, especially the working class, it appears more and more as a political system that serves as an instrument of the financial and business elites. Social democratic parties, which embraced the neo-liberal worldview, also suffered the consequences. They too have been discredited and are seen as part of the same corrupt ruling class elite as others.

It is in these circumstances that the far-right and neo-fascist forces have sought to exploit the discontent of the people, in general, with the neo-liberal order. They target migrants and religious and ethnic minorities to rouse xenophobia and anti-migrant feelings.

Globalised finance capital and neo-liberal regime everywhere have fostered identities based on ethnicity, religion and race. These have become the basis for rightwing identity politics and sectarian nationalisms. Different countries have different “others” to target -- Muslims in India, Kurds in Turkey, migrants, particularly from West Asia, in Europe and the United States, and so on.

Marxism helps us not only to understand the nature of this rightwing threat but also equips us with the political and ideological resources to fight them.

Basically it is through the class struggle that these rightwing forces can be combatted; this class struggle encompasses the struggle against imperialism and international finance capital. However, class struggle has primarily to be waged within national boundaries. As Marx and Engels wrote in the Communist Manifesto: “Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle. The proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie.”

Further, the class struggle cannot simply be seen as fighting for the economic demands of the basic classes. As Marx and Engels pointed out in the Communist Manifesto, “The class struggle is essentially a political struggle.”

In the Indian context, the fight against Hindutva communal forces is essentially a political and ideological struggle. Such a struggle gets qualitatively strengthened and acquires a mass character when it is harnessed to the struggle against the neo-liberal order.

In different parts of the world, the struggle against the rightwing offensive and against the divisive forces unleashed by capitalist globalization is bringing to the fore a renewed Left politics distinct from the politics of liberal democracy and compromised social democracy. We have seen such stirrings in the platform of Jeremy Corbyn of the Labour Party in Britain, the Democratic Socialists under the leadership of Bernie Sanders in the United States, the Left front in France, and the new popular movements like the gilet jaunes (yellow jackets), the environmental movements and others.

These are yet initial and tentative steps towards bringing the working class and the working people on to the centre-stage of political events. As Eric Hobsbawm wrote in his last book: “Once again the time has come to take Marx seriously.”