G Mamatha

THE other day, I was helping my child in learning paryayvachi shabd (synonyms) in Hindi. The children in the class were taught that the synonym for stree (woman) is abala (the meek). I was trying to convince my child that this is wrong and in fact this should be brought to the notice of the concerned teacher. In spite of the best of my efforts, my child, all of Class V too was not convinced that women are not meek and refused to discuss this with the teacher. This made me think about how dominant ideologies influence and mould our generations, right from their childhood. How true is the statement that no glass is half full. The other half too is full with air, which exists irrespective of our conscious efforts. Similar is the case of patriarchal hegemony over our society.

And then it had happened – that interview of Mukesh Singh, not a Page Three celebrity, or our elected representative, but one who is convicted for his role in the now infamous December 16 gang-rape incident in Delhi. The government had asked the television channels not to broadcast the interview, a part of the documentary made for the BBC. According to media reports, in that interview, the convicted Mukesh Singh had shared his 'outlook towards women': “Housework and housekeeping is for girls, not roaming in discos and bars at night doing wrong things, wearing wrong clothes. About 20 per cent of girls are good...A decent girl won't roam around at nine o'clock at night. A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy...People had a right to teach them a lesson...When being raped, she shouldn't fight back. She should just be silent and allow the rape. Then they'd have dropped her off after 'doing her', and only hit the boy...The death penalty will make things even more dangerous for girls. Now when they rape, they won't leave the girl like we did. They will kill her. Before, they would rape and say, 'Leave her, she won't tell anyone.' Now when they rape, especially the criminal types, they will just kill the girl. Death”.

The said documentary is not just about Mukesh Singh, but there are others too in it. Among them is Gaurav, who had raped a five-year-old girl. He recounted in explicit detail how he had pulled her knickers off but left her dress on, muffled her screams with his big hand, but left her nose free to breathe and described, in vivid detail, 'the child's huge terrified eyes and casually pointed out' that “she didn't even know what was being inserted”. When questioned how he could do this to a five-year-old girl, he said: “She was a beggar girl. Her life was of no value”.

Lest you condone the acts of these two persons as 'perverts', who are exceptions in our exemplary society, here is something more. ML Sharma, a lawyer defending the accused, stated in the documentary: “In our society, we never allow our girls to come out from the house after 6:30 or 7:30 or 8:30 in the evening with any unknown person...You are talking about man and woman as friends. Sorry, that doesn't have any place in our society. We have the best culture. In our culture, there is no place for a woman”. (Emphasis added) Sharma, of course is not alone. He has friends. AP Singh, another lawyer was already reported for saying: “If my daughter or sister engaged in pre-marital activities and disgraced herself and allowed herself to lose face and character by doing such things, I would most certainly take this sort of sister or daughter to my farmhouse, and in front of my entire family, I would put petrol on her and set her alight”.

Such is the attitude towards women in our society. Remember that Sharma, Singh, Mukesh or Gaurav are not specimens, but representatives of a deeper malaise. Recap the statements given by various politicians, celebrities and even members of the women's commissions on these issues and we can easily understand the depth of the morass that has set in the society, which requires a thorough cleansing.

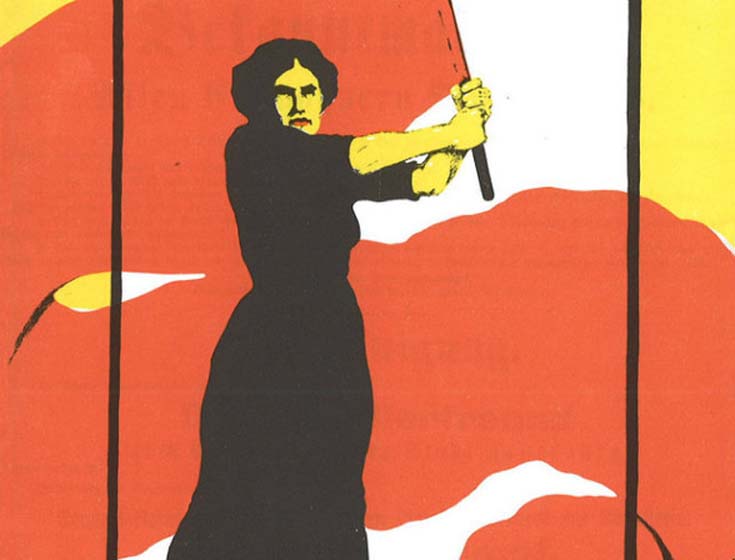

Everywhere around us – in our offices, neighbourhoods and homes – we find misogynists, who neither value women, nor their work. There are two kinds of rapists in a society: one, the kind of Mukesh and Gaurav, who physically assault and rape women; two, those who move around us with forked tongues, who psychologically assault women and try to debase them. They speak sweet, but act nonsense, like the Sangh Parivar. In fact, how sweet did the present BJP government heads speak – beti bachao abhyan (save the girl child campaign), empowering women (the under-current theme of our Republic Day parade), etc, etc. Cometh the time of budget and they stand exposed. Both these kinds are products of the same patriarchal school of oppression and should be fought against. This in fact is the true message of the International Women's Day and this indeed is the true dream of the massive spontaneous protests that erupted after the December 16 incident. It is upon us to realise them. Heidi Hartmann, economist, had written: “Men have more to lose than their chains”. How true! And it is upon us to help them.

WOMEN’S ECONOMIC STATUS

FACTS AND FIGURES

EVIDENCE from a range of countries shows that increasing the share of household income controlled by women, either through their own earnings or cash transfers, changes spending in ways that benefit children. Increasing women and girls’ education contributes to higher economic growth. Increased educational attainment accounts for about 50 per cent of the economic growth in OECD countries over the past 50 years, of which over half is due to girls having had access to higher levels of education and achieving greater equality in the number of years spent in education between men and women.

But, for the majority of women, significant gains in education have not translated into better labour market outcomes. Globally, women participate in labour markets on an unequal basis with men. In 2013, the male employment-to-population ratio stood at 72.2 per cent, while the ratio for females was 47.1 per cent.

Women in most countries earn on average only 60 to 75 per cent of men’s wages. Women are more likely to be wage workers and unpaid family workers, and more likely to engage in low-productivity activities and to work in the informal sector. Women are often viewed as economic dependents, and are more likely to be in unorganized sectors or not represented in unions.

It is calculated that women could increase their income globally by up to 76 per cent if the employment participation gap and the wage gap between women and men were closed. This is calculated to have a global value of $17 trillion.

Women bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work. Women devote 1 to 3 hours more a day to housework than men; 2 to 10 times the amount of time a day to care (for children, elderly, and the sick), and 1 to 4 hours less a day to market activities. In the European Union, 25 per cent of women report care and other family and personal responsibilities as the reason for not being in the labour force, versus only three per cent of men.

When paid and unpaid work are combined, women in developing countries work more than men, with less time for education, leisure, political participation and self-care. Despite some improvements over the last 50 years, in virtually every country, men spend more time on leisure each day while women spend more time doing unpaid housework.

Women are more likely than men to work in informal employment. In South Asia, over 80 per cent of women in non-agricultural jobs are in informal employment, in sub-Saharan Africa, 74 per cent, and in Latin America and the Caribbean, 54 per cent. In rural areas, many women derive their livelihoods from small-scale farming, almost always informal and often unpaid.

More women than men work in vulnerable, low-paid, or undervalued jobs. As of 2013, 49.1 per cent of the world’s working women were in vulnerable employment, often unprotected by labour legislation, compared to 46.9 per cent of men. Women were far more likely than men to be in vulnerable employment in East Asia (50.3 per cent versus 42.3 per cent), South-East Asia and the Pacific (63.1 per cent versus 56 per cent), South Asia (80.9 per cent versus 74.4 per cent), North Africa (54.7 per cent versus 30.2 per cent), the Middle East (33.2 per cent versus 23.7 per cent) and Sub-Saharan Africa (nearly 85.5 per cent versus 70.5 per cent).

Gender differences in laws affect both developing and developed economies, and women in all regions. Almost 90 per cent of 143 economies studied have at least one legal difference restricting women’s economic opportunities. Of those, 79 economies have laws that restrict the types of jobs that women can do. Husbands can object to their wives working and prevent them from accepting jobs in 15 economies.

Ethnicity and gender interact to create especially large pay gaps for minority women. In 2013 in the US, women of all major racial and ethnic groups earn less than men of the same group, and also earn less than white men. Hispanic women’s median earnings were $541 per week of full-time work, only 61.2 per cent of white men’s median weekly earnings, but 91.1 per cent of the median weekly earnings of Hispanic men (because Hispanic men also have low earnings). The median weekly earnings of black women were $606, only 68.6 per cent of white men’s earnings, but 91.3 per cent of black men’s median weekly earnings, which are also fairly low.

Women comprise an average of 43 per cent of the agricultural labour force in developing countries, varying across regions from 20 per cent or less in Latin America to 50 per cent or more in parts of Asia and Africa. But women farmers control less land than do men, and also have limited access to inputs, seeds, credits, and extension services. Less than 20 per cent of landholders are women. Gender differences in access to land and credit affect the relative ability of female and male farmers and entrepreneurs to invest, operate to scale, and benefit from new economic opportunities.

Women are responsible for household food preparation in 85-90 per cent of cases surveyed in a wide range of countries.

Women, especially those in poverty, appear more vulnerable in the face of natural disasters. A recent study of 141 countries found that more women than men die from natural hazards and disasters.

Women and children bear the main negative impacts of fuel and water collection and transport, with women in many developing countries spending from 1 to 4 hours a day collecting biomass for fuel. A study of time and water poverty in 25 sub-Saharan African countries estimated that women spend at least 16 million hours a day collecting drinking water; men spend 6 million hours; and children, 4 million hours. Gender gaps in domestic and household work, including time spent obtaining water and fuel and processing food, are intensified in contexts of economic crisis, environmental degradation, natural disasters, and inadequate infrastructure and services.

Source: www.unwomen.org