G Mamatha

NEARLY 40 percent of girls are in higher education in our country. Many of us take our education as granted – as something of a normal progression. If at all some of us are forced to discontinue our studies, we think it is because of the economic conditions of our families. Of course, many of us are also forced out of education, due to the lecherous behaviour of our so-called 'stronger sex', eve-teasing and sexual harassment. In other words, those of us fortunate enough to continue with our education, think that it is thanks to our familial support, we are able to pursue our dreams. But, this is only one half of the story.

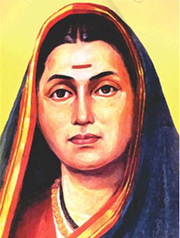

The other half, which is largely untold, is what is very important. Applauding Malala, who was given the Nobel Peace Prize because of her defiant spirit to continue with her education, many of us might have thanked that there is no Taliban in our country to pass diktats and try to force girls out of education. In order to understand the real reasons that secured us our rights – which we take for granted – we need to take a brief recourse to history. We should not forget that ours is a country, which has Manu and his dharmasastras, which explicitly stated: “If a woman should happen to merely overhear recitations of Vedic mantras by chance, hot molten glass should be poured into her ears”. It took the lives of many social reformers to challenge these codes and argue for the girls' right to education. We might have read about the lives of some of them, like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Raja Rammohan Roy, and others. Towering above all of them and indeed rightly called 'social revolutionary' (yes, not a social reformer) is a humble woman from Maharashtra, who, due to the prevailing biases in the society, is not given her entire due. This is Savitribai Phule.

Who is Savitribai Phule? Many might not be aware. Of those few who might be aware, many would answer, 'she is the wife of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule'. This sort of an introduction is indeed a grave affront to the great woman that she is. It can as well be said that Jyotiba Phule is Savitribai's husband. Savitribai was born on January 3, 1831 and as was the custom of that period, married to Jyotiba at a young age of nine years. Jyotiba too was a child, aged only thirteen. Encouraged by Jyotiba, Savitri went to school and got trained as a teacher. She became the first Indian woman teacher, headmistress and later an educator who ran many schools, specially for the girls and the mahars and mangs. For this crime of educating girls and dalits, she had to brave extreme harassment from the upper caste people. Upper caste youth used to waylay and abuse her. They used to throw dung at her. Undeterred by all these threats and harassment, she continued with her objective. Savitribai was so courageous, convinced and committed to her work that she always used to carry a spare sari along with her to the school, so that she can change the dirtied sari and teach the children. Once she even slapped the upper caste youth who used to harass her on her way to school. This had forced them to tail up and never bother her again.

For Savitribai, education did not mean a knowledge of alphabets. As she herself states: “We will teach our children and ourselves to learn. Receive knowledge and become wise to discern”. Imbibed in this understanding is the rationale aspect of education that empowers a person to 'discern' what is wrong and what is right. Education for her also meant acquiring knowledge to challenge the existing biases in the society and providing with the necessary courage to question the discrimination on the basis of caste and gender. It is this awareness that she had roused among the girls and dalits that made the upper castes fear and oppose her vehemently.

Savitribai and Jyotiba faced opposition not only from the outside society, but also from within their own families. Jyotiba's family pressurised them to give up their activities, but in vain. So they disowned them. Similarly Savitribai's family too tried to wean her away from her chosen path. In one of the letters she had written to Jyotiba, she narrates how she had to argue with her brother, who tried to dissuade her. With the force of her arguments and reasoning, she could convince her brother and mother and made them accept her work of educating girls and dalits.

From the above incident, two aspects speak volumes about the character of Savitribai. One, she emerges as probably the first woman in our country to write a letter to her husband, in which she shares her experiences with him. Two, arguing with her brother and mother, she does not state that she was following the footsteps of her husband as a 'faithful' wife. As a woman convinced of her work, she argues her case on its own merits and wins them over, instead of taking shelter behind the traditional concept of a 'true pativrata' – 'wife following in the footsteps of husband'. Here we find her as an individual with her own mind and standing to her ground.

In another letter she had written to Jyotiba, she narrates an incident about a brahmin boy who fell in love with a dalit girl. When the lovers were caught and were about to be murdered by the villagers, Savitribai, bravely entered in the midst of the mob, saved both of them and sent them to Jyotiba. Here we find Savitribai not just as an 'idealistic woman', but also as one who was ready to 'fight it on the streets' in defence of the ideals she believed to be right.

She also played an active role in the Satyashodhak Samaj established by Jyotiba Phule. Apart from education of girl children, the Samaj had worked for widow re-marriages, ran orphanages to care for children of widows and many other such activities. The Samaj had questioned the role of brahmins, rituals and their dominance on the society. The conduct of the first civil marriage in our country also goes to the credit of the Phule's and the Samaj. The Phule's had written alternate marriage rituals that require both the bride and the bridegroom to take an oath. In that way, Savitribai stands true to her exhortation: “Awake, arise and educate. Smash traditions – liberate”. Compare this with the 'pride' among a section of our society, who celebrate their marriages with elaborate rituals and traditions. This points to the need for continuing the work initiated by Savitribai.

From her work we understand how she was against recognising caste differences among human beings and thus had naturally encouraged inter-caste marriages. To acknowledge the radical nature of her work, we should not forget those times and particularly locate them in the context of the present days' 'honour killings' and the discourse on inter-caste marriages. In Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh, even today we find khap panchayats issuing diktats against the girls' right to choose their spouse, which are backed by many narrow minded political parties. Similarly, in Tamilnadu, we find a political outfit openly campaigning against inter-caste marriages.

Savitribai actively worked during the severe famine that had affected the region at that time. She had organised many relief activities, collected food and money and donated to the poor and needy. Riots broke out in the region for whatever meagre food that was available. When the district collector sent some white police officers to control those riots, they had arrested the volunteers of Samaj, who were conducting relief operations. Hearing this, Savitribai, rushed to the collector, explained the activities of the Samaj and got the volunteers released. Not only that, she also forced the collector to reprimand the white police officers and also got the government to sanction cart loads of food for the affected region and people.

The selfless sacrificial spirit of Savitribai can be understood from the fact that when plague had affected the region and people were dying of the disease and even medical professionals were refusing to treat the infected persons, she stood in the forefront caring for them. She bravely carried a plague infected person, tied to her back to the hospital and got the doctors attend to him and ensure that he is cured of the infection. In the process, she herself got infected by the disease and ultimately lost her life on 10.03.1897. This once again demonstrates how courageous Savitribai is and also reiterates the fact that unlike many others, she is not a person of words, but a person of deeds. It is these qualities that distinguish her from other 'reformers'.

Savitribai administered the Satyashodhak Samaj ably after the death of Jyotiba as its president. She also wrote poetry on the social evils of that period and exhorted the people to raise against them. Above all she practiced what she preached. She even led the funeral procession of her husband, a revolutionary act for that times. She was an eternal optimist, who expressed her confidence in putting an end to the brahmincal domination over the society and also ushering a future society that does not discriminate on the basis of caste. In one of her letters to Jyotiba she concludes: “We shall overcome and success will be ours in the future. The future belongs to us”.

It is upon us today to realise her dreams – to ensure that caste discrimination is brought to an end and human beings are all treated equally, without prejudice to their caste or class of birth. It is upon us to ensure that her life and work is made aware to all the citizens of our country. It is upon us to force the government to introduce a lesson on her life and work in all the school textbooks, so that children are aware of her immense sacrifice. That is a pledge we need to take on this occasion of her 184th birth anniversary.