Dare – To Dream, Fight and Change the World

R Arun Kumar

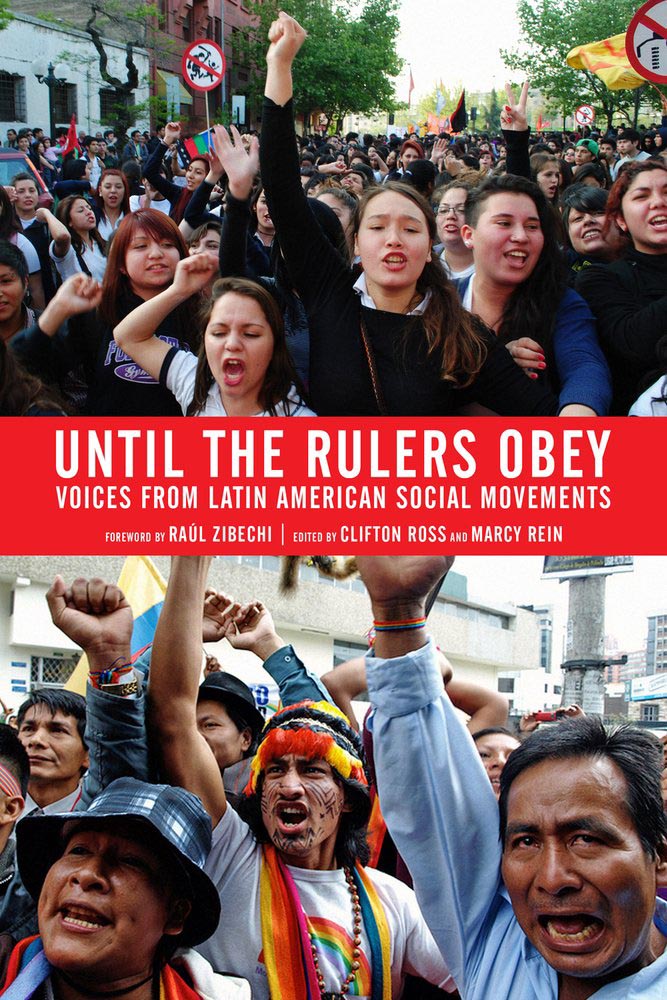

IN the recently concluded elections to various States in Latin America – Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay and El Salvador – the parties that were credited to have ushered in a 'pink tide', retained office. These victories are indeed significant, because many ruling parties (both Social Democrat and Conservative) across the world are losing elections in these times of global economic crises. To understand what separates these governments in Latin America and the challenges that they are facing, the recently published Until the Rulers Obey, Voices from Latin American Social Movements is extremely useful.

The book covers all the Latin American countries and adopts an interesting format. A brief introductory overview of each country is followed by various interviews providing different perspectives about the developments in the respective countries. Though invariably there is a subjective element involved in choosing the interviewees, enough care is taken by the editors to ensure a broad representation. Moreover, the overview for each country also acquaints the reader with a brief historical background for a better understanding of the present developments. Both the overview and the interviews critically analyse the processes at work in these countries. They also attempt to provide the readers a glance into the world of Latin American social movements, how they are organised/function, their objectives, achievements and the current challenges.

ROLE OF

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

The way the social movements are organised in the continent provides us broadly with some useful information about how they succeeded in mobilising masses and played a role in the formation of 'progressive' governments. Many of the social movements, which started as issue based movements, slowly addressed all the aspects of peoples' lives by actively involving them. They took up their cultural, economic and social issues and involved them in debates, formulating slogans and choosing the course of action. Contrary to neo-liberal philosophy that advocates individualism, they identified the common threads that bind people together and built a culture of collectivism and community feeling among the people. Through giving the people a voice, they helped in resurrecting their self-esteem and building confidence not only in themselves, but also in their collective strength. Those movements that struck to these principles in practice are surviving, while those that confined these principles to papers, faded or are fading away.

The belief in the possibility of 'another world' unites the various social movements in these countries. However, they differ and intensely debate over how this world will be realised and what this realised world would be. These varied standpoints define their attitude towards the 'progressive', 'Left' governments in the region. Even the various communist and workers' parties across the world too are engaged in deciphering these developments and thus enriching their experiences. Until the Rulers Obey, a Leftist critique, is a welcome addition to the debate.

The character of the State and its transformation (of course, its ultimate withering) is always an intensely contested subject, both among the Marxists, socialists and their opponents. After the setback to socialism in the Soviet Union and East European countries, these debates have further intensified with an addition – whether capitalism can be transcended and its State structure transformed. Latin America countered the neo-liberal philosophy, best expressed in the phrase, There Is No Alternative (TINA), with massive mobilisations that shook the hegemony of the ruling classes and reignited the hope that an alternative is possible. As a result, in many of these countries, the seats of power were transferred from the ruling elites to the ordinary workers (Lula of Brazil), peasants (Mujica of Uruguay) and indigenous people (Morales of Bolivia).

Those who had come to power promising a radical shift, initiated some measures and floated new ideas and concepts – horizontalism (opposed to verticalism or hierarchy), bottom-up (opposed to top-down), community participation, participative democracy, party-less movements, etc, – which gained rapid currency. Bolivarian Socialism, 21st century socialism, joined the lexicon of alternatives to the current system and also to the 20th century socialism.

These ideas/concepts attracted attention world over due to the way the elected governments in the region set about achieving their objective of 'transforming' the society. This has indeed led to a debate about the character of these governments – whether they are systemic alternatives or alternatives within the system; whether these are transitional governments leading to the socialist stage or another variant of the social-democrat governments. As many of the activists interviewed in the book note, though Chavez was sincere about his commitment towards socialism, all those surrounding him are not completely with the idea. Some of them are political opportunists, eager to enjoy the fruits of power for personal aggrandisement. Moreover, the Venezuelan State bureaucracy did not lose its class character and is not entirely sympathetic to the idea of Bolivarian Socialism. Many a times the State machinery itself is an impediment in the implementation of the 'missions' introduced by the Chavez administration. Indeed, the bourgeoisie and oligarchy that is still a strong force in Venezuela is now called as 'Boligarchy' and 'Bolibourgeoisie'.

CHARACTER OF

THE STATE

The nature or character of the State is one of the three important and common threads that run through all the criticisms of the 'progressive', 'Left' governments in Latin America. The same criticism made in Venezuela is heard from the activists in Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Brazil and other countries. The interviewees in the book rightly point out that it is impossible to bring in 'socialism' in these countries by continuing with the inherited State apparatus.

Pointing to the stark inequalities in land holdings across the continent, the critics state that these governments have done precious little to change the status quo. Even in Venezuela, considered to be the most radical amongst all the other countries, the question of distributing land is still a major concern, nearly a decade and a half after Chavez had first come to power. Similar is the case in Brazil, where the MST (Movement of the Landless Workers) feels betrayed by the PT as it did not live true to its promise of land distribution.

Related with this is the second aspect – the policies pursued by these governments. Many of the interviewees point out that the social welfare schemes contributed to the reduction of poverty, illiteracy and also improved various health indicators. But all these, as they correctly point, are only subsidies or doles handed out to the poor and are not solutions that empower them to permanently come out of poverty. These measures make them dependent on the State and build a 'clientèle' to the current parties in power. Indeed there are examples of some military rulers/dictators providing subsidies and carrying our social welfare schemes in the continent. Even the right-wing government in Colombia is implementing welfare schemes, for whatever reason. These subsidies do not 'empower' people in the real sense, as they do not provide them control over the means of production.

One of the main activists in Argentina, where the famous worker occupation of factories took place, clearly states that though they are controlling the production as a collective, there are still many obstacles they are facing from the State. The question is, can the worker(s) exercise 'real power' by occupying one or few factories, in the midst of an entire economy remaining in the hands of the bourgeoisie? Answering in the negative, they say that though takeover of a factory might address some of their immediate issues like hunger, it does not solve all their life problems.

MODEL OF

DEVELOPMENT

The third aspect is the model of development these governments are pursuing. There is a strong criticism on the development model pursued by the governments of Bolivia, Ecuador and Brazil. The huge dams that are planned by these governments, the highways cutting across the Amazon are all opposed as going against the grain of what these parties profess on sustainable development and protection of indigenous rights. Many indigenous groups are raising against the permissions that these governments had given to mining companies (public they might be) and the mega projects that threaten their sensitive eco-system.

Until the Rulers Obey brings out all these aspects and the dilemma faced by the social movements and the Left today, particularly in the context of somebody considered as 'one-amongst-them' being in power. Many of them talk about the attitude the social movements and the Left need to adopt towards the popular governments – whether they should struggle or not – particularly with the lurking imperialist supported, right-wing parties trying to reap the benefit from these struggles. This dilemma is further compounded by the fact that those movements that did not launch struggles are losing their relevance as they are considered to have been co-opted by the government. And those who carry on with their struggles, are branded as part of the opposition, helping the right-wing forces. This is indeed an interesting aspect, which is of extreme relevance to our country and needs to be further studied.

MODE OF

STRUGGLE

This debate proceeds to another larger question – about the mode of struggle for social transformation. Many countries in Latin America have had a long history of waging armed guerrilla struggles against colonial occupiers and dictatorships. Now they are into electoral politics. The experiences of former guerrilla leaders who had given up the armed struggle and are now acting as governors to certain provinces in Colombia, give us an interesting perspective. With this rich experience, they debate the question of the path for an alternative society. Ortega's victory in Nicaragua, achieved through compromises with the centrist and certain right-wing forces, the compromises made by the FMLN in El Salvador (by choosing a sympathetic journalist Mauricio Funes) to attain presidency and Lula's watered down electoral campaign to secure his first victory – are all debated to show how Left is forced to tone down its agenda in order to attain electoral victories. They point out that this is not a 'strategic retreat' by the Left as it does not work towards implementing its original agenda once in power, but comprises a 'real retreat', as in order to ensure its re-election the Left continues to compromise, ultimately losing its identity.

From these experiences, some movements decided to keep away from elections, political parties and the State, while some got co-opted. On the other hand, there is a section which argues that parliaments and elections alone are not sufficient for bettering peoples' lives and what is needed is a thorough change in the State machinery. They argue that left to themselves, no government, however progressive it might be, will work for the benefit of the poor and marginalised. A constant struggle to pressurise the government is needed to ensure that it does not deviate from the path it had promised.

An important lacuna in the book is the absence of the role of the communist parties in the entire process taking shape in the continent. Communists, irrespective of their strength, are playing an important role, either as part of the government (like Brazil) or in organising popular struggles (in Chile). Historically, communists have played a prominent role in resisting dictatorships and organising working class and peasants. They had led guerrilla struggles in many countries. The book would have become wholesome if the editors attempted to incorporate at least some of these voices. This would have helped in understanding the reasons for the present state of communist parties in that part of the world.

Until the Rulers Obey, is not only about tactics and strategy adopted by social movements, but also is about personal stories of great grit and determination. This is a book for everyone who dares to dream, fight and change the world. As Noami Klein had said, this is a book we have been waiting for.