Gabriel García Márquez: Living to Tell the Tale

Sonya Surabhi Gupta

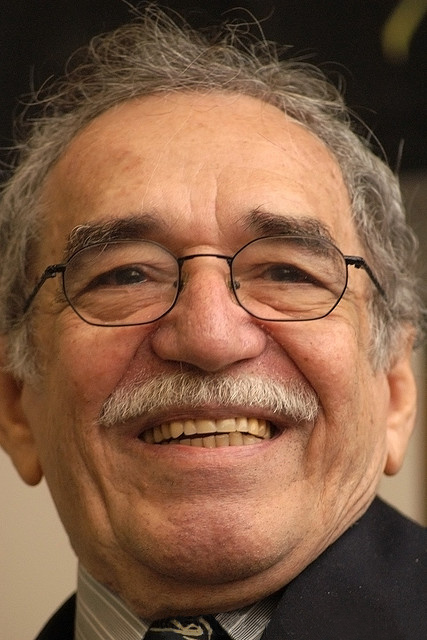

TEN days after his discharge from a hospital in Mexico City, Gabriel García Márquez, one of the greatest writers of our times, died on April 17, 2014 at the age of 87. Author of classic works such as One Hundred Years of Solitude, Love in the Times of Cholera, No One Writes to the Colonel, The Autumn of the Patriarch and Chronicle of a Death Foretold, he created the eternal and marvelous Macondo which, in the imagination of millions of his readers, became synonymous with Latin America. When he accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, García Márquez described Latin America as a "source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune. Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable."

The search for literary expression was therefore one of the foremost concerns of writers and poets in Latin America and it is in García Márquez’s narrative style, in his “magical realism” that Latin America found its most potent literary voice. When we today remember Gabriel García Márquez or “Gabo as he was popularly known, it is not as one of the world’s best novelist and writer alone, but also as a revolutionary, who stood firm in his belief that “it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of a utopia”. It was for his political convictions that he was exiled several times from Colombia, his country, and was denied US visas during years for his clear and forthright criticism of Washington's violent interventions from Vietnam to Chile.

An unflinching supporter of the Cuban revolution, he enjoyed a warm personal relationship with Comrade Fidel Castro. Fidel, in an article written in 2008, reminisces how when after the revolution triumphed in 1959, on suggestion of Che Guevara, a news agency was started – Prensa Latina – and when the agency hired the services of a modest Colombian journalist called Gabriel García Márquez, little did it know that “with the ‘colossal’ imagination of the son of a telegrapher in the post office of a small town in Colombia, lost among the banana plantations of a yankee fruit company,” it was hiring a future Nobel laureate.

García Márquez was born in Aracataca, a small Colombian town near the Caribbean coast, on March 6, 1927. He was the eldest of the 11 children of Luisa Santiaga Márquez and Gabriel Elijio García, a telegrapher and a wandering homeopathic pharmacist. Just after he was born, his parents left him with his maternal grandparents and moved to Barranquilla, where García Márquez's father opened a pharmacy, hoping to become rich. García Márquez was raised for 10 years by his grandmother and his grandfather, a retired colonel who fought in the devastating 1,000-Day War that hastened Colombia's loss of the Panamanian isthmus.

His grandmother’s tales would provide the inspiration for García Márquez's fictional style and Aracataca became the model for “Macondo,” the village surrounded by banana plantations at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains where One Hundred Years of Solitude is set. This epic 1967 novel sold more than 50 million copies in more than 25 languages. In India, his works have been translated into Malayalam, Bengali, Hindi, Punjabi and Kannada.

García Márquez's writing was constantly informed by his leftist political views, themselves forged in large part by a 1928 military massacre near Aracataca of banana workers striking against the United Fruit Company. He was also greatly influenced by the assassination two decades later of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a leftist presidential candidate. Beginning with those early days of political formation, through the churnings of the Cuban revolution, until his death, García Márquez remained a committed communist.

García Márquez suffered a strong official backlash to his story about how government corruption contributed to the disaster recounted in “Story of A Shipwrecked Sailor” (1955). When dictatorship seized power in Colombia, García Márquez was forced to move to Europe. After touring the Socialist Eastern Europe, he moved to Rome in 1955 to study cinema, a lifelong love. Then he moved to Paris, where he lived among intellectuals and artists exiled from the many Latin American dictatorships of the day.

García Márquez returned to Colombia in 1958 to marry Mercedes Barcha, a neighbor from childhood days. They had two sons, Rodrigo, a film director, and Gonzalo, a graphic designer.

After a 1981 run-in with Colombia's government in which he was accused of sympathizing with M-19 rebels and sending money to a Venezuelan guerrilla group, García Márquez moved to Mexico City, his main home for the rest of his life.

THREE PASSIONS: FICTION, JOURNALISM & CINEMA

García Márquez dedicated himself to three cultural passions all through his intense and committed life: his fictional works (novels and short stories), which opened for him the doors to posterity; cinema (scripts, adaptations, productions); and journalism (with several genres and different styles, from chronicles to investigative journalism, to political commentary, to film criticism). And this is, in addition to his love for music and plastic arts. In other words, as distinct from the majority of writers, of a solitary existence focused on themselves, García Márquez was an activist.

He founded his own institution of journalism, the Foundation for New Iberoamerican Journalism (FNPI) in 1994 with the help of UNESCO in Cartagena. The Foundation offers training and competitions to raise the standard of narrative and investigative journalism across Latin America. He was an early practitioner of the literary nonfiction that would become known as New Journalism.

As mentioned above, after the triumph of the Cuban revolution, he worked with the Cuban news agency, Prensa Latina. Before that, he had been editor of various magazines at different times but his militant journalism needs special mention. He was almost finishing his novel The Autumn of the Patriarch when the government of Salvador Allende in Chile was brought down in September 1973. García Márquez decided to temporarily give up literature, and along with a group of young Colombian intellectuals and journalists, he founded a political magazine called Alternativa which was published during six turbulent years from 1974 to 1980. He as well as the other intellectuals put in their personal money in this venture.

In 1975, García Márquez once again returned to Cuba and traveled extensively through the island and published three dispatches. He later wrote: “My idea was to write about how the Cubans broke the blockade within their homes. Not the work of the government or the state, but how the people themselves resolved the problems of kitchen, of washing clothes, of the needle-to-stitch, all these quotidian difficulties.” In 1976, he wrote an epic chronicle of the Cuban expedition in Africa, the first time a “third world” country had interposed itself in a conflict involving two superpowers. In the mean time, Central America was continuing its convulsive revolutionary process. García Márquez covered the Sandinista revolution for Alternativa.

In 1980, the magazine closed down and García Márquez returned to fiction, this time, with Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Later, already in his 70s, García Márquez fulfilled a lifelong dream, buying a majority interest in the Colombian newsmagazine Cambio with money from his Nobel. Before falling ill with lymphatic cancer in June 1999, the author contributed prodigiously to the magazine, including an article profiling Hugo Chávez in 1998. He also vividly portrayed how cocaine traffickers led by Pablo Escobar had shred the social and moral fabric of his native Colombia, kidnapping members of its elite, in News of a Kidnapping.

García Márquez’s love for cinema was no less. In 1986, he created his own institutions, the Foundation for New Latin American Cinema and the International School for Cinema and Television (EICTV) in San Antonio de Los Baños in Cuba where he offered his well known workshops on “How to Tell a Tale” in which he worked with the students on the ways of putting together a cinematic script. In fact, he had said on many occasions that at the beginning he wanted to be a film director and the only thing he has really studied is cinema (in 1955, he had taken admission in the Experimental Centre of Cinematography in Rome). He wrote about cinema as a columnist and wrote cinema as a scriptwriter.

To say it in a few words, we can distinguish between writers concerned about analyzing the relation between their own introspection and the structure of reality, on one hand, and those who seek to tease out from this labyrinth a direction, a path, that is, those who “live to tell the tale.” Gabriel García Márquez, the activist that he was, will always be remembered as the grand story-teller of our times, as the one who lived to tell the tale.